Casos Clínicos

PROBABLE ASOCIACION DE LOS INHIBIDORES DE LA TIROSINA QUINASA CON LA PERSISTENCIA DE CLONES ABERRANTES CON CROMOSOMA FILADELFIA NEGATIVO

Se describe el caso de un paciente con leucemia mieloide crónica que, durante el tratamiento con inhibidores de la tirosina quinasa de primera y segunda generación, presenta múltiples clones con anomalías cromosómicas.

Clasificación en siicsalud

Artículos originales > Expertos del Mundo >

página /dato/casiic.php/115090

Especialidades

Artículos originales > Expertos del Mundo >

página /dato/casiic.php/115090

Especialidades

Primera edición en siicsalud

31 de agosto, 2011

31 de agosto, 2011

PROBABLE ASOCIACION DE LOS INHIBIDORES DE LA TIROSINA QUINASA CON LA PERSISTENCIA DE CLONES ABERRANTES CON CROMOSOMA FILADELFIA NEGATIVO

(especial para SIIC © Derechos reservados)

(especial para SIIC © Derechos reservados)

Introducción

La leucemia mieloide crónica (LMC) se desencadena por la traslocación recíproca t(9;22)(q34;q11) del cromosoma Filadelfia (CF), en la cual el protooncogén ABL se fusiona con el gen BCR. El gen de fusión resultante (BCR-ABL) codifica una proteína oncogénica con actividad incrementada de proteína quinasa.1

El mesilato de imatinib (antes denominado STI571), el primer inhibidor de la tirosina quinasa con eficacia clínica, se une en forma directa con el dominio con actividad de tirosina quinasa de la proteína BCR-ABL, con inhibición de los eventos de señalización que conduce a la apoptosis de las células BCR-ABL positivas (Figura 1).2 Se ha probado que esta pequeña molécula de biodisponibilidad oral es altamente eficaz en el tratamiento de la LMC, con la inducción de remisión sostenida hematológica y citogenética en todas las fases de la enfermedad, lo que constituye una tasa poco frecuente de respuesta en la terapia del cáncer. El imatinib se encuentra actualmente aprobado como tratamiento de primera línea en los pacientes con LMC de reciente diagnóstico.3-4 A pesar de la destacada eficacia del imatinib, la duración de la respuesta permanece como uno de los mayores interrogantes, al igual que la potencial cura asociada con el medicamento. Por otra parte, puede persistir enfermedad residual detectable mediante la reacción en cadena de la polimerasa (PCR), con aparición de resistencia medicamentosa.5 Asimismo, dado que en la actualidad se recomienda mantener la terapia con imatinib en forma indefinida, surgen inquietudes relacionadas con la seguridad y la toxicidad del tratamiento a largo plazo. No se ha informado aún de un incremento en el riesgo de cáncer; sin embargo, hasta el 5% al 10% de los pacientes con LMC en fase crónica tratados con imatinib presentan cambios citogenéticos en las células con CF negativo.6-10 Presentamos aquí el caso de un paciente con LMC que adquirió múltiples cambios citogenéticos clonales en células CF negativas y describimos el efecto de los inhibidores de la tirosina quinasa de segunda generación sobre esos clones celulares.

Métodos Estudios de cariotipo y de hibridación de fluorescencia in situ

Se efectuaron estudios convencionales de citogenética en las células de la médula ósea en cultivos de 24 h por medio de técnicas convencionales. Los cariotipos se describieron de acuerdo con el International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature.11 Se definió como remisión citogenética completa (RCC) a la ausencia de células con CF positivo en la médula ósea. La presencia de anomalías cromosómicas se confirmó mediante pruebas de hibridación de fluorescencia in situ (FISH) en preparados de análisis citogenético disponibles comercialmente (LSI BCR/ABL1 en color dual, sondas de traslocación de fusión dual, sondas CEP 8 y CEP x/Y) según los protocolos de los fabricantes. Las señales de hibridación se visualizaron con un microscopio de epifluorescencia, con captura y digitalización de imágenes con un software especializado. Para cada sonda génica se evaluaron y clasificaron alrededor de 500 núcleos en interfase y 10 extensiones en metafase.

Estudios moleculares

Las pruebas de PCR cualitativas en tiempo real se efectuaron con ARN celular total extraído de la muestra de médula ósea con un reactivo específico, de acuerdo con las recomendaciones del fabricante. Se elaboraron cadenas de ADN complementario a partir de 2 µg de ARN total con un equipo de síntesis. Las pruebas de PCR cuantitativas en tiempo real para la determinación del nivel de transcriptos del gen BCR-ABL en sangre periférica se llevaron a cabo con un ensayo de monitoreo de la proteína BCR-ABL de acuerdo con el protocolo del fabricante.

Resultados

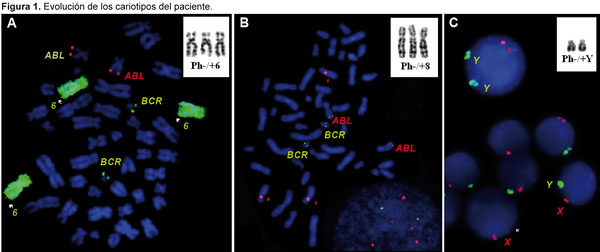

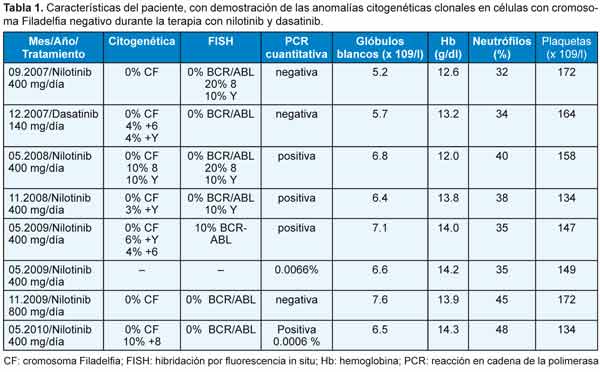

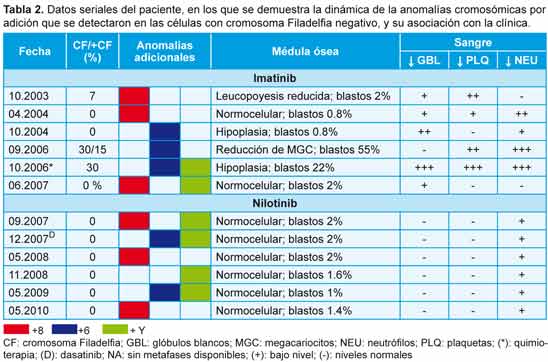

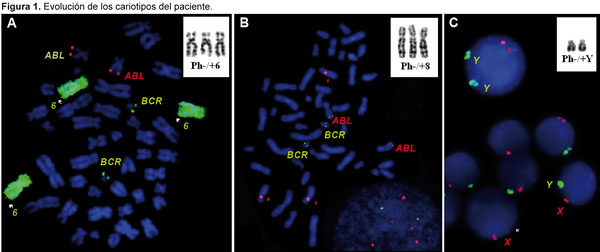

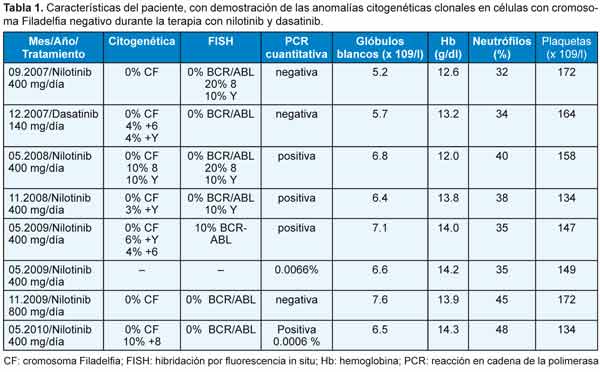

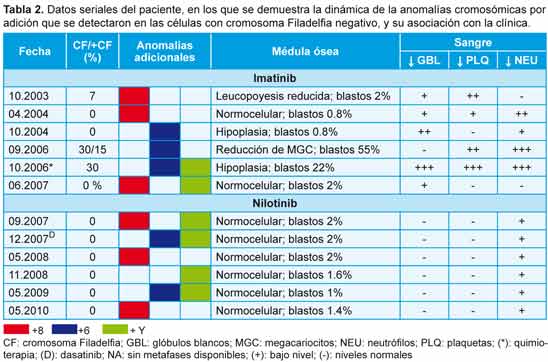

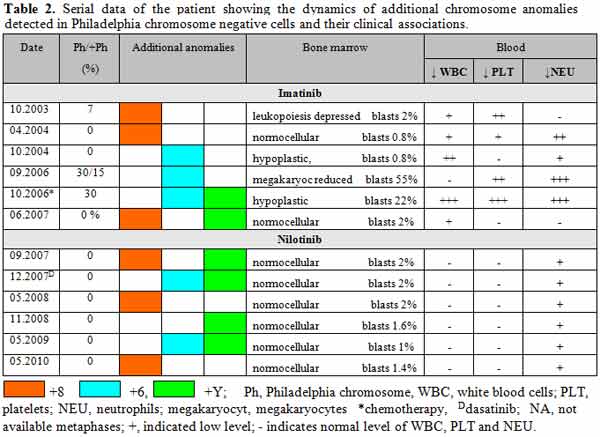

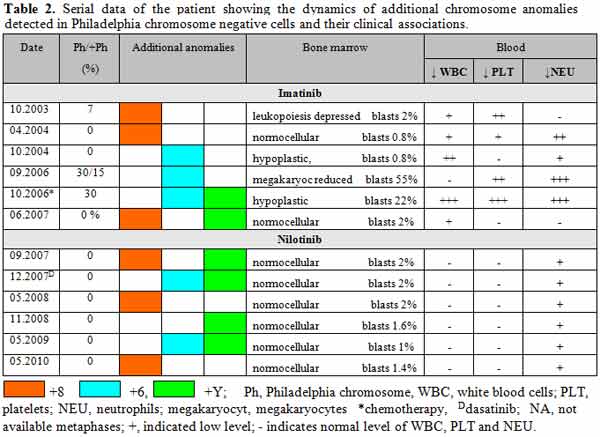

Se diagnosticó LMC con CF positivo en un varón de 43 años en 1998. Fue tratado de forma inicial con interferón alfa, sin respuesta citogenética, y desde 2002 se administró tratamiento con 400 mg/día de mesilato de imatinib. Se obtuvo respuesta citogenética casi completa 10 meses después (7% de metafases positivas para CF), pero con la aparición de un nuevo clon con CF positivo (trisomía 8 en las células de la médula ósea; figura 2A). La misma anomalía se observó 4 meses después cuando el paciente se encontraba en RCC (0% de metafases positivas para CF). A los 6 meses se identificó un nuevo hallazgo citogenético (un clon pequeño con CF negativo y trisomía del cromosoma 6) y los análisis por FISH confirmaron que las células carecían del reordenamiento BCR-ABL (Figura 2B). Como informamos en nuestro primer estudio,12 la aparición de un cromosoma 6 adicional se acompañó de hipoplasia de la médula ósea y signos de displasia, así como con citopenias en sangre periférica. En septiembre de 2006, el enfermo presentó una crisis blástica linfoide caracterizada por un CF adicional y trisomía 6 en las células con CF negativo en sus metafases. La quimioterapia se asoció con una reducción del 30% en las metafases con CF positivo, pero al mismo tiempo se detectaron 2 clones con CF negativo en la médula ósea, uno de ellos con trisomía 6 y el restante con un cromosoma Y adicional (Figura 2C). Para ese entonces, el recuento de plaquetas se había reducido a 42 x 109/l y los glóbulos blancos habían disminuido a 1.1 x 109/l, en asociación con neutropenia (16% de neutrófilos) y anemia (hemoglobina = 8.7 g/dl), mientras que en la médula ósea se reconoció hipoplasia con disminución de los megacariocitos. Durante la subsecuente terapia con 600 mg diarios de imatinib, las células CF positivas desaparecieron de la médula ósea y la PCR en tiempo real permitió confirmar la desaparición del clon que expresaba el gen BCR-ABL. Durante la remisión completa se reconocieron 2 clones CF negativos no relacionados entre sí, en un caso con trisomía 8 y, en el restante, con un cromosoma Y adicional (Tabla 1). Desde junio de 2007 se administró tratamiento con 400 mg diarios de nilotinib, con normalización de los recuentos celulares y desaparición del clon que expresaba el gen BCR-ABL; sin embargo, en el 20% de las células se observó trisomía del cromosoma 8 y reaparición del clon con un cromosoma Y adicional. Tres meses más tarde, después de la terapia ulterior con 140 mg diarios de dasatinib, se detectó la reaparición de los clones con CF negativos, ya sea con trisomía 6 o con un cromosoma Y adicional. Luego del tratamiento con nilotinib, se describió el resurgimiento de clones CF negativos con trisomía 8, trisomía 6 o cromosoma Y adicional en diferentes momentos, a pesar de la desaparición de las células CF positivas (Tabla 2). Actualmente, el enfermo continúa recibiendo nilotinib con buena tolerabilidad, con la excepción de un incremento asintomático de la bilirrubina no conjugada y un leve aumento de la alanina aminotransferasa. Los niveles de los trascriptos del gen BCR-ABL estimados por PCR cuantitativa en tiempo real fueron de 0.006% en una muestra de sangre periférica obtenida en mayo de 2010.

Discusión

La aparición de clones anormales con CF negativo en pacientes con LMC que reciben tratamiento con inhibidores de la tirosina quinasa ha sido observada previamente en algunos estudios, si bien su origen y su valor pronóstico aún son inciertos.13-15 Si bien estas aberraciones en general son transitorias y desaparecen con la terapia continua, en raras ocasiones pueden presentarse de manera repetida. La mayoría de estas anomalías son aberraciones numéricas, características de las leucemias mieloides agudas de novo o asociadas con el tratamiento o bien de los síndromes mielodisplásicos, e incluyen la trisomía 8 y las monosomías 7 y 5. Además, se ha informado de algunos casos de mielodisplasia y leucemia mieloide aguda en sujetos sin tratamientos relevantes previos al imatinib, lo que incrementa la posibilidad de un papel causal de este medicamento al menos en una proporción de los pacientes.8,16-18 En este contexto, uno de los principales interrogantes consiste en establecer si la aparición de un clon anormal con CF negativo permite predecir en forma directa u orientar hacia la aparición de una nueva enfermedad, o bien si representa un fenómeno transitorio sin repercusión clínica.

En nuestro paciente, la aparición de metafases con trisomía 8 y CF negativo se observó después de 14 meses del inicio de la terapia con imatinib. El surgimiento de la trisomía 8 en células con CF negativo se asoció con citopenias en sangre periférica, trombocitopenia y menor leucopoyesis. Un año después, el clon con trisomía 8 y CF negativo fue sustituido por un nuevo clon con anormalidades citogenéticas (CF negativo y trisomía 6). En forma similar a los casos descritos previamente, el surgimiento de la trisomía 6 en las metafases con CF negativo fue precedido y asociado con citopenias en sangre periférica, neutropenia e hipoplasia medular, por lo que se sugiere un papel causal del tratamiento sobre la hiperplasia medular y la posible participación del cromosoma 6 adicional en la patogénesis en nuestro paciente.19-22

Acaso el interrogante más enigmático de esta observación es el origen de los múltiples clones anormales con CF negativo. La descripción de 2 clones diferentes, uno de ellos con trisomía 8 y CF negativo y el otro con traslocación (9;22), sólo sugiere un origen biclonal, respaldado por la reaparición de células con CF negativo y trisomía 8 a los 6 meses (0% de células CF positivas). El surgimiento de clones con CF negativo y trisomía 6 en sujetos con RCC confirmada, así como la coexistencia de metafases con trisomía 6 y CF negativos y positivos durante la progresión de la enfermedad, apoyan la hipótesis de que los clones con CF negativo se originan a partir de una células progenitora con inestabilidad genética. Asimismo, la aparición de 3 clones sin correlación citogenética (uno con traslocación t[9;22], otro con trisomía 6 y el restante con CF negativo y un cromosoma Y adicional) también indica un origen policlonal de las células patológicas con CF positivo y CF negativo en nuestro paciente.

La persistencia de 3 clones con anomalías citogenéticas (trisomías 6 y 8, cromosoma Y adicional) a lo largo de 7 años de observación avala la posibilidad de que el tratamiento específico por sí mismo indujo o facilitó el surgimiento de estos clones no relacionados con citogenética anormal en nuestro paciente. De todos modos, el mecanismo no es claro; nuestras observaciones sugieren la posibilidad de un efecto mutagénico directo del tratamiento prolongado en este enfermo. Si bien la terapia con inhibidores de la tirosina quinasa de segunda generación se asoció con buena eficacia en nuestro paciente, ni el tratamiento con nilotinib ni el uso de dasatinib permitieron la erradicación de los cambios citogenéticos clonales en células con CF negativo. Dado que las aberraciones clonales detectadas en este paciente fueron anomalías cromosómicas numéricas, nuestros hallazgos permiten sugerir un papel causal de los inhibidores de la tirosina quinasa en la inducción de las aneuploidías. Esta posibilidad puede sustentarse en los recientes hallazgos de estudios in vitro en los que se demostró la inducción de aberraciones en cromosomas y centrosomas en asociación con defectos en el huso mitótico e inestabilidad genética en fibroblastos normales de animales y seres humanos tratados con imatinib y nilotinib.23-25 Aunque la aparición de anomalías citogenéticas en clones con CF negativo ocurre sólo en un pequeño subgrupo de pacientes, nuestros resultados destacan la importancia de control cercano de los enfermos con LMC que responden a la terapia con inhibidores de la tirosina quinasa, con posibles repercusiones pronósticas y terapéuticas.

No declarados.

La leucemia mieloide crónica (LMC) se desencadena por la traslocación recíproca t(9;22)(q34;q11) del cromosoma Filadelfia (CF), en la cual el protooncogén ABL se fusiona con el gen BCR. El gen de fusión resultante (BCR-ABL) codifica una proteína oncogénica con actividad incrementada de proteína quinasa.1

El mesilato de imatinib (antes denominado STI571), el primer inhibidor de la tirosina quinasa con eficacia clínica, se une en forma directa con el dominio con actividad de tirosina quinasa de la proteína BCR-ABL, con inhibición de los eventos de señalización que conduce a la apoptosis de las células BCR-ABL positivas (Figura 1).2 Se ha probado que esta pequeña molécula de biodisponibilidad oral es altamente eficaz en el tratamiento de la LMC, con la inducción de remisión sostenida hematológica y citogenética en todas las fases de la enfermedad, lo que constituye una tasa poco frecuente de respuesta en la terapia del cáncer. El imatinib se encuentra actualmente aprobado como tratamiento de primera línea en los pacientes con LMC de reciente diagnóstico.3-4 A pesar de la destacada eficacia del imatinib, la duración de la respuesta permanece como uno de los mayores interrogantes, al igual que la potencial cura asociada con el medicamento. Por otra parte, puede persistir enfermedad residual detectable mediante la reacción en cadena de la polimerasa (PCR), con aparición de resistencia medicamentosa.5 Asimismo, dado que en la actualidad se recomienda mantener la terapia con imatinib en forma indefinida, surgen inquietudes relacionadas con la seguridad y la toxicidad del tratamiento a largo plazo. No se ha informado aún de un incremento en el riesgo de cáncer; sin embargo, hasta el 5% al 10% de los pacientes con LMC en fase crónica tratados con imatinib presentan cambios citogenéticos en las células con CF negativo.6-10 Presentamos aquí el caso de un paciente con LMC que adquirió múltiples cambios citogenéticos clonales en células CF negativas y describimos el efecto de los inhibidores de la tirosina quinasa de segunda generación sobre esos clones celulares.

Métodos Estudios de cariotipo y de hibridación de fluorescencia in situ

Se efectuaron estudios convencionales de citogenética en las células de la médula ósea en cultivos de 24 h por medio de técnicas convencionales. Los cariotipos se describieron de acuerdo con el International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature.11 Se definió como remisión citogenética completa (RCC) a la ausencia de células con CF positivo en la médula ósea. La presencia de anomalías cromosómicas se confirmó mediante pruebas de hibridación de fluorescencia in situ (FISH) en preparados de análisis citogenético disponibles comercialmente (LSI BCR/ABL1 en color dual, sondas de traslocación de fusión dual, sondas CEP 8 y CEP x/Y) según los protocolos de los fabricantes. Las señales de hibridación se visualizaron con un microscopio de epifluorescencia, con captura y digitalización de imágenes con un software especializado. Para cada sonda génica se evaluaron y clasificaron alrededor de 500 núcleos en interfase y 10 extensiones en metafase.

Estudios moleculares

Las pruebas de PCR cualitativas en tiempo real se efectuaron con ARN celular total extraído de la muestra de médula ósea con un reactivo específico, de acuerdo con las recomendaciones del fabricante. Se elaboraron cadenas de ADN complementario a partir de 2 µg de ARN total con un equipo de síntesis. Las pruebas de PCR cuantitativas en tiempo real para la determinación del nivel de transcriptos del gen BCR-ABL en sangre periférica se llevaron a cabo con un ensayo de monitoreo de la proteína BCR-ABL de acuerdo con el protocolo del fabricante.

Resultados

Se diagnosticó LMC con CF positivo en un varón de 43 años en 1998. Fue tratado de forma inicial con interferón alfa, sin respuesta citogenética, y desde 2002 se administró tratamiento con 400 mg/día de mesilato de imatinib. Se obtuvo respuesta citogenética casi completa 10 meses después (7% de metafases positivas para CF), pero con la aparición de un nuevo clon con CF positivo (trisomía 8 en las células de la médula ósea; figura 2A). La misma anomalía se observó 4 meses después cuando el paciente se encontraba en RCC (0% de metafases positivas para CF). A los 6 meses se identificó un nuevo hallazgo citogenético (un clon pequeño con CF negativo y trisomía del cromosoma 6) y los análisis por FISH confirmaron que las células carecían del reordenamiento BCR-ABL (Figura 2B). Como informamos en nuestro primer estudio,12 la aparición de un cromosoma 6 adicional se acompañó de hipoplasia de la médula ósea y signos de displasia, así como con citopenias en sangre periférica. En septiembre de 2006, el enfermo presentó una crisis blástica linfoide caracterizada por un CF adicional y trisomía 6 en las células con CF negativo en sus metafases. La quimioterapia se asoció con una reducción del 30% en las metafases con CF positivo, pero al mismo tiempo se detectaron 2 clones con CF negativo en la médula ósea, uno de ellos con trisomía 6 y el restante con un cromosoma Y adicional (Figura 2C). Para ese entonces, el recuento de plaquetas se había reducido a 42 x 109/l y los glóbulos blancos habían disminuido a 1.1 x 109/l, en asociación con neutropenia (16% de neutrófilos) y anemia (hemoglobina = 8.7 g/dl), mientras que en la médula ósea se reconoció hipoplasia con disminución de los megacariocitos. Durante la subsecuente terapia con 600 mg diarios de imatinib, las células CF positivas desaparecieron de la médula ósea y la PCR en tiempo real permitió confirmar la desaparición del clon que expresaba el gen BCR-ABL. Durante la remisión completa se reconocieron 2 clones CF negativos no relacionados entre sí, en un caso con trisomía 8 y, en el restante, con un cromosoma Y adicional (Tabla 1). Desde junio de 2007 se administró tratamiento con 400 mg diarios de nilotinib, con normalización de los recuentos celulares y desaparición del clon que expresaba el gen BCR-ABL; sin embargo, en el 20% de las células se observó trisomía del cromosoma 8 y reaparición del clon con un cromosoma Y adicional. Tres meses más tarde, después de la terapia ulterior con 140 mg diarios de dasatinib, se detectó la reaparición de los clones con CF negativos, ya sea con trisomía 6 o con un cromosoma Y adicional. Luego del tratamiento con nilotinib, se describió el resurgimiento de clones CF negativos con trisomía 8, trisomía 6 o cromosoma Y adicional en diferentes momentos, a pesar de la desaparición de las células CF positivas (Tabla 2). Actualmente, el enfermo continúa recibiendo nilotinib con buena tolerabilidad, con la excepción de un incremento asintomático de la bilirrubina no conjugada y un leve aumento de la alanina aminotransferasa. Los niveles de los trascriptos del gen BCR-ABL estimados por PCR cuantitativa en tiempo real fueron de 0.006% en una muestra de sangre periférica obtenida en mayo de 2010.

Discusión

La aparición de clones anormales con CF negativo en pacientes con LMC que reciben tratamiento con inhibidores de la tirosina quinasa ha sido observada previamente en algunos estudios, si bien su origen y su valor pronóstico aún son inciertos.13-15 Si bien estas aberraciones en general son transitorias y desaparecen con la terapia continua, en raras ocasiones pueden presentarse de manera repetida. La mayoría de estas anomalías son aberraciones numéricas, características de las leucemias mieloides agudas de novo o asociadas con el tratamiento o bien de los síndromes mielodisplásicos, e incluyen la trisomía 8 y las monosomías 7 y 5. Además, se ha informado de algunos casos de mielodisplasia y leucemia mieloide aguda en sujetos sin tratamientos relevantes previos al imatinib, lo que incrementa la posibilidad de un papel causal de este medicamento al menos en una proporción de los pacientes.8,16-18 En este contexto, uno de los principales interrogantes consiste en establecer si la aparición de un clon anormal con CF negativo permite predecir en forma directa u orientar hacia la aparición de una nueva enfermedad, o bien si representa un fenómeno transitorio sin repercusión clínica.

En nuestro paciente, la aparición de metafases con trisomía 8 y CF negativo se observó después de 14 meses del inicio de la terapia con imatinib. El surgimiento de la trisomía 8 en células con CF negativo se asoció con citopenias en sangre periférica, trombocitopenia y menor leucopoyesis. Un año después, el clon con trisomía 8 y CF negativo fue sustituido por un nuevo clon con anormalidades citogenéticas (CF negativo y trisomía 6). En forma similar a los casos descritos previamente, el surgimiento de la trisomía 6 en las metafases con CF negativo fue precedido y asociado con citopenias en sangre periférica, neutropenia e hipoplasia medular, por lo que se sugiere un papel causal del tratamiento sobre la hiperplasia medular y la posible participación del cromosoma 6 adicional en la patogénesis en nuestro paciente.19-22

Acaso el interrogante más enigmático de esta observación es el origen de los múltiples clones anormales con CF negativo. La descripción de 2 clones diferentes, uno de ellos con trisomía 8 y CF negativo y el otro con traslocación (9;22), sólo sugiere un origen biclonal, respaldado por la reaparición de células con CF negativo y trisomía 8 a los 6 meses (0% de células CF positivas). El surgimiento de clones con CF negativo y trisomía 6 en sujetos con RCC confirmada, así como la coexistencia de metafases con trisomía 6 y CF negativos y positivos durante la progresión de la enfermedad, apoyan la hipótesis de que los clones con CF negativo se originan a partir de una células progenitora con inestabilidad genética. Asimismo, la aparición de 3 clones sin correlación citogenética (uno con traslocación t[9;22], otro con trisomía 6 y el restante con CF negativo y un cromosoma Y adicional) también indica un origen policlonal de las células patológicas con CF positivo y CF negativo en nuestro paciente.

La persistencia de 3 clones con anomalías citogenéticas (trisomías 6 y 8, cromosoma Y adicional) a lo largo de 7 años de observación avala la posibilidad de que el tratamiento específico por sí mismo indujo o facilitó el surgimiento de estos clones no relacionados con citogenética anormal en nuestro paciente. De todos modos, el mecanismo no es claro; nuestras observaciones sugieren la posibilidad de un efecto mutagénico directo del tratamiento prolongado en este enfermo. Si bien la terapia con inhibidores de la tirosina quinasa de segunda generación se asoció con buena eficacia en nuestro paciente, ni el tratamiento con nilotinib ni el uso de dasatinib permitieron la erradicación de los cambios citogenéticos clonales en células con CF negativo. Dado que las aberraciones clonales detectadas en este paciente fueron anomalías cromosómicas numéricas, nuestros hallazgos permiten sugerir un papel causal de los inhibidores de la tirosina quinasa en la inducción de las aneuploidías. Esta posibilidad puede sustentarse en los recientes hallazgos de estudios in vitro en los que se demostró la inducción de aberraciones en cromosomas y centrosomas en asociación con defectos en el huso mitótico e inestabilidad genética en fibroblastos normales de animales y seres humanos tratados con imatinib y nilotinib.23-25 Aunque la aparición de anomalías citogenéticas en clones con CF negativo ocurre sólo en un pequeño subgrupo de pacientes, nuestros resultados destacan la importancia de control cercano de los enfermos con LMC que responden a la terapia con inhibidores de la tirosina quinasa, con posibles repercusiones pronósticas y terapéuticas.

No declarados.

Persistence of clonal chromosome aberrations in Philadelpia-negative cells in a chronic myeloid leukemia patient during treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors

(especial para SIIC © Derechos reservados)

(especial para SIIC © Derechos reservados)

Introduction

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is initiated by a reciprocal Philadelphia chromosome (Ph) translocation t(9;22)(q34;q11) that fuses the ABL proto-oncogene to the BCR gene. The resulting BCR-ABL fusion gene encodes an oncogenic protein with enhanced tyrosine kinase activity.1 Imatinib mesylate (formerly STI571; Glivec®, Gleevec®; Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Basel, Switzerland), the first clinically successful tyrosine kinase inhibitor directly binds to the tyrosine kinase domain of BCR-ABL protein and blocks downstream signalling events, leading to apoptosis of BCR-ABL+ cells (Figure 1).2 This orally bioavailable small molecule has proven highly effective in CML treatment, leading to sustained hematologic and cytogenetic remissions in all phases of CML, a response rate rarely seen in cancer therapy. Imatinib is now approved for the first-line therapy of newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia patients.3-4 Despite the dramatic efficacy of imatinib, the durability of responses remains one of the major questions as is potential for cure with imatinib. Moreover, residual disease persists, measurable by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and drug resistance emerges.5 In addition, as it is currently recommended that imatinib therapy be continued indefinitely, ongoing questions relate to safety and toxicity of long-term therapy. No increased cancer risk has yet been documented; however, up to 5% to 10% of patients with chronic phase CML treated with imatinib develop cytogenetic changes in Philadelphia chromosome-negative (Ph-) cells.6-10 We report here a case of a CML patient who acquired multiple clonal cytogenetic changes in Ph-chromosome negative cells and describe the effect of second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors on Ph negative clones.

Methods Karyotyping and fluorescence in situ hybridization studies

Conventional cytogenetic studies were performed on bone marrow cells from 24-hour cultures using standard techniques and karyotypes were described according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature.11 Complete cytogenetic remission (CCR) was defined as no Philadelphia-positive (Ph+) cells in the bone marrow. The presence of chromosomal abnormalities was confirmed by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) on slides prepared for cytogenetic analysis using commercially available LSI BCR/ABL1 Dual Color, Dual Fusion Translocation Probe, CEP 8 and CEP X/Y probes (Vysis, Downers Grove, IL, USA) using manufacturer's protocol. Hybridization signals were visualized by a Zeiss Axioskop epifluorescence microscope and images were captured and digitally recorded by Isis software (MetaSystem, Germany). Approximately 500 interphase nuclei and 10 metaphase spreads were examined and scored for each probe. Molecular studies

Qualitative RT-PCR was performed from total cellular RNA extracted from the bone marrow sample using the Trizol LS reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Gaithersburg) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. cDNA was prepared from 2 µg of total RNA with the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Gaithersburg). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR for determination of BCR-ABL transcript levels in peripheral blood samples was performed using the GeneXpert System performed with BCR-ABL monitor assay (Cepheid, US) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Results

A 43-year-old male was diagnosed with Ph-positive CML in 1998. Initially treated with interpheron-a but without cytogenetic response and from 2002 therapy with imatinib mesylate (400 mg?day), was administrated. A near complete cytogenetic response was achieved 10 month later (7% Ph-positive metaphases), but with an emergence of a new Ph-negative clone, trisomy 8 in bone marrow cells (Figure 2A). The same anomaly was observed 4 months later while he was in complete cytogenetic remission (0% Ph+ metaphases). Six month later, a new cytogenetic finding, a small Ph-negative clone, trisomy of chromosome 6 was found and FISH analysis confirmed that the cells lacked the BCR-ABL rearrangement (Figure 2B). Reported in our earliest study,12 the appearance of extra chromosome 6 was accompanied with hypoplastic bone marrow and dysplastic features in addition to peripheral blood cytopenia. In September 2006, the patient developed lymphoid blast crisis characterized by an extra Ph chromosome and trisomy 6 in Ph-negative metaphases. Treatment with chemotherapy resulted in reduction of Ph+ metaphases to 30%, but at the same time two Ph-negative clones were detected in the bone marrow, one with trisomy 6 and one with an extra Y chromosome (Figure 2C). By then, his platelet counts were reduced to 42 ? 109?L, his WBC was reduced to 1.1x109?L associated with neutropenia (neutrophils 16%) and anemia (Hb 8.7 g?dL), while bone marrow was interpreted as hypoplastic with depressed megakaryocytes. During subsequent therapy with imatinib (600mg/day), his Ph-positive cells disappeared from the bone marrow and RT-PCR confirmed the disappearance of the BCR-ABL clone. While in complete remission, two Ph-negative, unrelated clones were observed, one with trisomy 8, the other with an extra chromosome Y (Table 1). From June 2007, therapy with nilotinib was administrated (400 mg/day), resulting in normalization of blood cell counts and disappearance of the BCR-ABL clone; however in 20% of cells trisomy of chromosome 8 and reappearance of +Y clone was found. 3 months later, after subsequent treatment with dasatinib (140 mg/day), reappearance of the +6/Ph- and +Y/Ph- clones were detected. During subsequent treatment with nilotinib, the reappearance of +8/Ph, +6/Ph- and +Y/Ph- clones was observed at multiple time points, despite disappearance of the Ph chromosome (Table 2). At present, the patient continues on therapy with nilotinib and he tolerates the treatment well, except for asymptomatic un-conjugated bilirubin increase and mild ALT increase. His BCR-ABL transcript level assessed by Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was 0.006 % in peripheral blood sample in May 2010.

Discussion

The emergence of abnormal Ph-negative clones in CML patients receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy has previously been observed by several studies, although their origin and prognostic significance are still uncertain.13-15 While these aberrations are frequently transient and disappear with continued therapy, in rare instances they may be presented on repeated occasions. Most of these anomalies are numerical aberrations, typical of de novo and treatment-related acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes including trisomy 8, monosomy 7, and monosomy 5. In addition, several cases of myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukaemia have been documented in patients without any significant therapy before imatinib, raising the possibility of a causative role of imatinib, in at least in a proportion of patients.8,16-18 In this regard, one of the main questions to address is whether the emergence of an abnormal Ph-negative clone directly predicts or signals the development of a new disorder, or it represents a transient phenomenon and has no clinical significance. In our patient, the emergence of Ph- trisomy 8 metaphases was seen after 14 months from the start of imatinib therapy. The appearance of trisomy 8 in Ph negative cells was associated with peripheral blood cytopenia, thrombocytopenia and depressed leukopoiesis. One year later, the Ph-/+8 clone was replaced by a new cytogenetically abnormal Ph-/+6clone. Similar to previously described cases, the appearance of trisomy 6 in Ph-negative metaphases was preceded and associated with peripheral cytopenia, neutropenia and marrow hypoplasia, suggesting the causative role of treatment in marrow hyperplasia and the possible role of the gain of chromosome 6 in the pathogenesis in our patient.19-22 Perhaps the most intriguing question raised by our observation is the origin of multiple Ph-negative abnormal clones in our patient. The observation of two different clones, one with Ph-/+8 and one with t(9;22) only suggest biclonal origin, supported by the reappearance of +8/Ph- cells 6 month later (0% Ph+). The emergence of Ph-/+6 clones in a patient with documented complete cytogenetic remission and the coexistence of Ph+ and Ph-/+6 metaphases during disease progression further supports the theory that these Ph- clones arose from a genetically unstable progenitor cell. In addition, the emergence of a three cytogenetically unrelated clones, one with t(9;22), another with trisomy 6 and a third clone with Ph-/+Y is also indicative of multiclonal origin of Ph+ and Ph- pathologic cells in our patient.

The persistence of three different cytogenetically abnormal +6, +8 and +Y clones over the 7 years observation period further supports the possibility that a specific treatment itself induced or favored the acquisition of these cytogenetically unrelated clones in our patient. The mechanism is not clear however; our observations suggest the possibility of a direct mutagenic effect of prolonged treatment in our patient. While treatment with second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors has shown good efficacy in our patient, neither treatment with nilotinib neither treatment with dasatinib resulted in eradication of Ph- clonal cytogenetic changes. Since clonal aberrations detected in our patient were numerical chromosome anomalies, our findings suggest a causative role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in induction of aneuploidy. This possibility may be further supported by recent findings of in vitro studies that showed induction of centrosome and chromosomal aberrations associated with mitotic spindle defects and genetic instability in normal human and animal fibroblasts that were treated with imatinib and nilotinib.23-25 Although the development of cytogenetically abnormal Ph-negative clones occurs only in a small subset of patients, our findings highlight the importance of close monitoring of CML patients responding to tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy with possible prognostic and therapeutic implications.

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is initiated by a reciprocal Philadelphia chromosome (Ph) translocation t(9;22)(q34;q11) that fuses the ABL proto-oncogene to the BCR gene. The resulting BCR-ABL fusion gene encodes an oncogenic protein with enhanced tyrosine kinase activity.1 Imatinib mesylate (formerly STI571; Glivec®, Gleevec®; Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Basel, Switzerland), the first clinically successful tyrosine kinase inhibitor directly binds to the tyrosine kinase domain of BCR-ABL protein and blocks downstream signalling events, leading to apoptosis of BCR-ABL+ cells (Figure 1).2 This orally bioavailable small molecule has proven highly effective in CML treatment, leading to sustained hematologic and cytogenetic remissions in all phases of CML, a response rate rarely seen in cancer therapy. Imatinib is now approved for the first-line therapy of newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia patients.3-4 Despite the dramatic efficacy of imatinib, the durability of responses remains one of the major questions as is potential for cure with imatinib. Moreover, residual disease persists, measurable by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and drug resistance emerges.5 In addition, as it is currently recommended that imatinib therapy be continued indefinitely, ongoing questions relate to safety and toxicity of long-term therapy. No increased cancer risk has yet been documented; however, up to 5% to 10% of patients with chronic phase CML treated with imatinib develop cytogenetic changes in Philadelphia chromosome-negative (Ph-) cells.6-10 We report here a case of a CML patient who acquired multiple clonal cytogenetic changes in Ph-chromosome negative cells and describe the effect of second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors on Ph negative clones.

Methods Karyotyping and fluorescence in situ hybridization studies

Conventional cytogenetic studies were performed on bone marrow cells from 24-hour cultures using standard techniques and karyotypes were described according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature.11 Complete cytogenetic remission (CCR) was defined as no Philadelphia-positive (Ph+) cells in the bone marrow. The presence of chromosomal abnormalities was confirmed by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) on slides prepared for cytogenetic analysis using commercially available LSI BCR/ABL1 Dual Color, Dual Fusion Translocation Probe, CEP 8 and CEP X/Y probes (Vysis, Downers Grove, IL, USA) using manufacturer's protocol. Hybridization signals were visualized by a Zeiss Axioskop epifluorescence microscope and images were captured and digitally recorded by Isis software (MetaSystem, Germany). Approximately 500 interphase nuclei and 10 metaphase spreads were examined and scored for each probe. Molecular studies

Qualitative RT-PCR was performed from total cellular RNA extracted from the bone marrow sample using the Trizol LS reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Gaithersburg) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. cDNA was prepared from 2 µg of total RNA with the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Gaithersburg). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR for determination of BCR-ABL transcript levels in peripheral blood samples was performed using the GeneXpert System performed with BCR-ABL monitor assay (Cepheid, US) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Results

A 43-year-old male was diagnosed with Ph-positive CML in 1998. Initially treated with interpheron-a but without cytogenetic response and from 2002 therapy with imatinib mesylate (400 mg?day), was administrated. A near complete cytogenetic response was achieved 10 month later (7% Ph-positive metaphases), but with an emergence of a new Ph-negative clone, trisomy 8 in bone marrow cells (Figure 2A). The same anomaly was observed 4 months later while he was in complete cytogenetic remission (0% Ph+ metaphases). Six month later, a new cytogenetic finding, a small Ph-negative clone, trisomy of chromosome 6 was found and FISH analysis confirmed that the cells lacked the BCR-ABL rearrangement (Figure 2B). Reported in our earliest study,12 the appearance of extra chromosome 6 was accompanied with hypoplastic bone marrow and dysplastic features in addition to peripheral blood cytopenia. In September 2006, the patient developed lymphoid blast crisis characterized by an extra Ph chromosome and trisomy 6 in Ph-negative metaphases. Treatment with chemotherapy resulted in reduction of Ph+ metaphases to 30%, but at the same time two Ph-negative clones were detected in the bone marrow, one with trisomy 6 and one with an extra Y chromosome (Figure 2C). By then, his platelet counts were reduced to 42 ? 109?L, his WBC was reduced to 1.1x109?L associated with neutropenia (neutrophils 16%) and anemia (Hb 8.7 g?dL), while bone marrow was interpreted as hypoplastic with depressed megakaryocytes. During subsequent therapy with imatinib (600mg/day), his Ph-positive cells disappeared from the bone marrow and RT-PCR confirmed the disappearance of the BCR-ABL clone. While in complete remission, two Ph-negative, unrelated clones were observed, one with trisomy 8, the other with an extra chromosome Y (Table 1). From June 2007, therapy with nilotinib was administrated (400 mg/day), resulting in normalization of blood cell counts and disappearance of the BCR-ABL clone; however in 20% of cells trisomy of chromosome 8 and reappearance of +Y clone was found. 3 months later, after subsequent treatment with dasatinib (140 mg/day), reappearance of the +6/Ph- and +Y/Ph- clones were detected. During subsequent treatment with nilotinib, the reappearance of +8/Ph, +6/Ph- and +Y/Ph- clones was observed at multiple time points, despite disappearance of the Ph chromosome (Table 2). At present, the patient continues on therapy with nilotinib and he tolerates the treatment well, except for asymptomatic un-conjugated bilirubin increase and mild ALT increase. His BCR-ABL transcript level assessed by Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was 0.006 % in peripheral blood sample in May 2010.

Discussion

The emergence of abnormal Ph-negative clones in CML patients receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy has previously been observed by several studies, although their origin and prognostic significance are still uncertain.13-15 While these aberrations are frequently transient and disappear with continued therapy, in rare instances they may be presented on repeated occasions. Most of these anomalies are numerical aberrations, typical of de novo and treatment-related acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes including trisomy 8, monosomy 7, and monosomy 5. In addition, several cases of myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukaemia have been documented in patients without any significant therapy before imatinib, raising the possibility of a causative role of imatinib, in at least in a proportion of patients.8,16-18 In this regard, one of the main questions to address is whether the emergence of an abnormal Ph-negative clone directly predicts or signals the development of a new disorder, or it represents a transient phenomenon and has no clinical significance. In our patient, the emergence of Ph- trisomy 8 metaphases was seen after 14 months from the start of imatinib therapy. The appearance of trisomy 8 in Ph negative cells was associated with peripheral blood cytopenia, thrombocytopenia and depressed leukopoiesis. One year later, the Ph-/+8 clone was replaced by a new cytogenetically abnormal Ph-/+6clone. Similar to previously described cases, the appearance of trisomy 6 in Ph-negative metaphases was preceded and associated with peripheral cytopenia, neutropenia and marrow hypoplasia, suggesting the causative role of treatment in marrow hyperplasia and the possible role of the gain of chromosome 6 in the pathogenesis in our patient.19-22 Perhaps the most intriguing question raised by our observation is the origin of multiple Ph-negative abnormal clones in our patient. The observation of two different clones, one with Ph-/+8 and one with t(9;22) only suggest biclonal origin, supported by the reappearance of +8/Ph- cells 6 month later (0% Ph+). The emergence of Ph-/+6 clones in a patient with documented complete cytogenetic remission and the coexistence of Ph+ and Ph-/+6 metaphases during disease progression further supports the theory that these Ph- clones arose from a genetically unstable progenitor cell. In addition, the emergence of a three cytogenetically unrelated clones, one with t(9;22), another with trisomy 6 and a third clone with Ph-/+Y is also indicative of multiclonal origin of Ph+ and Ph- pathologic cells in our patient.

The persistence of three different cytogenetically abnormal +6, +8 and +Y clones over the 7 years observation period further supports the possibility that a specific treatment itself induced or favored the acquisition of these cytogenetically unrelated clones in our patient. The mechanism is not clear however; our observations suggest the possibility of a direct mutagenic effect of prolonged treatment in our patient. While treatment with second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors has shown good efficacy in our patient, neither treatment with nilotinib neither treatment with dasatinib resulted in eradication of Ph- clonal cytogenetic changes. Since clonal aberrations detected in our patient were numerical chromosome anomalies, our findings suggest a causative role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in induction of aneuploidy. This possibility may be further supported by recent findings of in vitro studies that showed induction of centrosome and chromosomal aberrations associated with mitotic spindle defects and genetic instability in normal human and animal fibroblasts that were treated with imatinib and nilotinib.23-25 Although the development of cytogenetically abnormal Ph-negative clones occurs only in a small subset of patients, our findings highlight the importance of close monitoring of CML patients responding to tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy with possible prognostic and therapeutic implications.

Adriana Zamecnikova, Kuwait Cancer Control Center Department of Hematology Laboratory of Cancer Genetics, 70653, Shuwaikh, Kuwait,

e-mail: annaadria@yahoo.com

1. Quintas-Cardama A, Cortes J. Molecular biology of bcr-abl1-positive chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 113:1619-1630, 2009.

2. Konig H, Holtz M, Modi H, Manley P, Holyoake TL, Forman SJ, et al. Enhanced BCR-ABL kinase inhibition does not result in increased inhibition of downstream signaling pathways or increased growth suppression in CML progenitors. Leukemia 22 4:748-55, 2008.

3. Druker BJ. Translation of the Philadelphia chromosome into therapy for CML. Blood 112(13):4808-4817, 2008.

4. Hochhaus A, O'Brien SG, Guilhot F, Druker BJ, Branford S, Foroni L, et al. Six-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for the first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 23(6):1054-61, 2009.

5. Branford S. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Molecular Monitoring in Clinical Practice. Hematology 1:376-383, 2007.

6. Bumm T, Muller C, Al-Ali HK, Krohn K, Shepherd P, Schmidt E, et al. Emergence of clonal cytogenetic abnormalities in Ph- cells in some CML patients in cytogenetic remission to imatinib but restoration of polyclonal hematopoiesis in the majority. Blood 101(5):1941-9, 2003.

7. Espinet B, Oliveira AC, Boque C, Domingo A, Alonso E, Sole F. Clonal cytogenetic abnormalities in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in complete cytogenetic response to imatinib mesylate. Haematologica 90:556-558, 2005.

8. Deininger MW, Cortes J, Paquette R, Park B, Hochhaus A, Baccarani M et al. The prognosis for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia who have clonal cytogenetic abnormalities in philadelphia chromosome-negative cells. Cancer 110:1509-1519, 2007.

9. Loriaux M, Deininger M. Clonal cytogenetic abnormalities in Philadelphia chromosome negative cells in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with imatinib. Leuk Lymphoma 45:2197-2203, 2004.

10. Terre C, Eclache V, Rousselot P, et al. Report of 34 patients with clonal chromosomal abnormalities in Philadelphia negative cells during imatinib treatment of Philadelphia positive chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 18:1340-1346, 2004.

11. ISCN 1995: an international system for human cytogenetic nomenclature (1995). Mitelman F, editor. Basel: S. Karger, 1995.

12. Zámeníkova A, Al-Bahar S Pandita R. Trisomy 6 in a CML patient receiving imatinib mesylate therapy. Leuk Res 32:1454-1457, 2008.

13. Goldberg SL, Madan RA, Rowley SD, Pecora AL, Hsu JW, Tantravahi R. Myelodysplastic subclones in chronic myeloid leukemia: implications for imatinib mesylate therapy. Blood 101:781-781, 2003.

14. Baldazzi C, Luatti S, Marzocchi G, Stacchini M, Gamberini C, Castagnetti F, et al. Emergence of clonal chromosomal abnormalities in Philadelphia negative hematopoiesis in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with nilotinib after failure of imatinib therapy. Leuk Res 33(12):e218-20, 2009.

15. Fabarius A, Haferlach C, Müller MC, Erben P, Lahaye T, Giehl M et al. Dynamics of cytogenetic aberrations in Philadelphia chromosome positive and negative hematopoiesis during dasatinib therapy of chronic myeloid leukemia patients after imatinib failure. Haematologica 92:834, 2007.

16. Kovitz C, Kantarjian H, Garcia-Manero G, Abruzzo LV, Cortes J. Myelodysplastic syndromes and acute leukemia developing after imatinib mesylate therapy for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 108:2811-2813, 2006.

17. Navarro JT, Feliu E, Grau J, Espinet B, Colomer D, Ribera JM et al. Monosomy 7 with severe myelodysplasia developing during imatinib treatment of Philadelphia-positive chronic myeloid leukemia: two cases with a different outcome. Am J Hematol 82:849-851, 2007.

18. Jabbour E, Kantarjian HM, Abruzzo LV, O'Brien S, Garcia-Manero G, Verstovsek S et al. Chromosomal abnormalities in Philadelphia chromosome negative metaphases appearing during imatinib mesylate therapy in patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase. Blood 110:2991-2995, 2007.

19. Cervetti G, Carulli G, Galimberti S, Azzarà A, Buda G, Orciuolo E et al. Transitory marrow aplasia during Imatinib therapy in a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res 32:194-195, 2008.

20. LeMarbre G, Schinstock C, Hoyer R, Krook J, Tefferi A. Late onset aplastic anemia during treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia with imatinib mesylate. Leuk Res 31:414-415, 2007.

21. Moormeier JA, Rubin CM, Le Beau MM, Vardiman JW, Larson RA. Trisomy 6: A recurring cytogenetic abnormality associated with marrow hypoplasia. Blood 77:1397-1401, 1991.

22. Yilmaz Y, Klein R, Qumsiyeh MB. Trisomy 6 acquired in lymphoid blast transformation of chronic myelocytic leukemia with t(9;22) Cancer Genet Cytogenet 145:86-87, 2003.

23. Giehl FM, Rebacz B, Kramer A, Frank O, Haferlach C, Duesberg P, Hehlmann R, Seifarth W, Hochhaus A. Centrosome aberrations and G1 phase arrest after in vitro and in vivo treatment with the SRC/ABL inhibitor dasatinib. Haematologica 93:1145-1154, 2008. 24. Fabarius A, Giehl M, Frank O, Duesberg P, Hochhaus A, Hehlmann R et al. Induction of centrosome and chromosome aberrations by imatinib in vitro. Leukemia 19:1573-1578, 2005.

25. Fabarius A, Giehl M, Frank O, Spiess B, Zheng C, Müller MC. Centrosome aberrations after nilotinib and imatinib treatment in vitro are associated with mitotic spindle defects and genetic instability. Br J Haematol 138:369-373, 2007.

Artículos publicados por el autor

(selección)

Al- Bahar S, Zámecníkova A. Frequency and type of chromosomal abnormalities in childhood ALL patients in Kuwait: A six-year retrospective study. Med Princ Pract 19:176-181, 2010

Zamecnikova A . Targetting the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia as a model of rational drug dsign in cancer. Expert Reviews of Hematology 3:45-56, 2010

Al-Bahar S, Zámecníkova A, Pandita R. A novel variant translocation t(6;8;21)(p21;q22;q22) leading to AML/ETO fusion in acute myeloid leukemia. Gulf Journal of Oncology. 5:56-59, 2008

Zámecníkova A, Al- Bahar S. Simultaneous occurrence of MLL and RARA rearrangements in a pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia patient. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 52:671-674, 2009

Al- Bahar S, Zámecníkova A. Frequency and type of chromosomal abnormalities in childhood ALL patients in Kuwait: A six-year retrospective study. Med Princ Pract 19:176-181, 2010

Zamecnikova A . Targetting the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia as a model of rational drug dsign in cancer. Expert Reviews of Hematology 3:45-56, 2010

Al-Bahar S, Zámecníkova A, Pandita R. A novel variant translocation t(6;8;21)(p21;q22;q22) leading to AML/ETO fusion in acute myeloid leukemia. Gulf Journal of Oncology. 5:56-59, 2008

Zámecníkova A, Al- Bahar S. Simultaneous occurrence of MLL and RARA rearrangements in a pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia patient. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 52:671-674, 2009

Está expresamente prohibida la redistribución y la redifusión de todo o parte de los

contenidos de la Sociedad Iberoamericana de Información Científica (SIIC) S.A. sin

previo y expreso consentimiento de SIIC.

ua91218