Casos Clínicos

LA ENTEROSCOPIA ASISTIDA POR BALON ES DE UTILIDAD PARA DIAGNOSTICAR LAS ESTENOSIS DEL INTESTINO DELGADO

La enteroscopia asistida por balón demostró ser útil y segura para el diagnóstico y para dirigir el tratamiento de las estenosis del intestino delgado.

Coautores

Juergen Pohl* Christian Ell*

MD PhD, HSK Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden, Alemania*

Juergen Pohl* Christian Ell*

MD PhD, HSK Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden, Alemania*

Clasificación en siicsalud

Artículos originales > Expertos del Mundo >

página /dato/casiic.php/104997

Especialidades

Artículos originales > Expertos del Mundo >

página /dato/casiic.php/104997

Especialidades

Primera edición en siicsalud

19 de enero, 2010

19 de enero, 2010

LA ENTEROSCOPIA ASISTIDA POR BALON ES DE UTILIDAD PARA DIAGNOSTICAR LAS ESTENOSIS DEL INTESTINO DELGADO

(especial para SIIC © Derechos reservados)

(especial para SIIC © Derechos reservados)

Introducción

La enfermedad de Crohn (EC) se complica frecuentemente con síntomas obstructivos secundarios a estenosis del intestino delgado. Estas estenosis usualmente no podían ser accesibles mediante la endoscopia convencional. Con el advenimiento de la enteroscopia de doble balón (EDB), ha sido posible no sólo realizar una evaluación diagnóstica de todo el intestino delgado, sino también la dilatación endoscópica con balón de las estenosis del intestino delgado.

En 2007 hicimos un informe acerca del rendimiento diagnóstico y terapéutico de la EDB, también conocida como enteroscopia de empuje y acortamiento (“push-and-pull enteroscopy”), para las estenosis sintomáticas del intestino delgado en la EC.1 Pudimos demostrar que la EDB es útil para el diagnóstico y para dirigir el tratamiento en los pacientes con estenosis del intestino delgado asociadas con la EC. La dilatación con balón durante la EDB demostró ser segura y efectiva. Por lo tanto puede considerarse como una alternativa a la cirugía en pacientes seleccionados con estenosis refractarias al tratamiento médico y con baja actividad inflamatoria en las estenosis.

Describimos el caso de una mujer de 47 años tratada repetidamente en nuestra unidad de endoscopia por estenosis del intestino delgado por enfermedad de Crohn. El caso ejemplifica la combinación de distintas estrategias para el tratamiento de las estenosis del intestino delgado.

Caso clínico

Cuando se presentó en nuestra unidad por primera vez, en 2004, la paciente tenía EC de 20 años de evolución. Se habían realizado varias resecciones de segmentos de intestino delgado debidas a estenosis con obstrucciones secundarias. Sólo quedaban aproximadamente 100 cm de intestino delgado residual. Durante tres años la paciente recibió tratamiento con corticoides (en forma intermitente) y azatioprina.

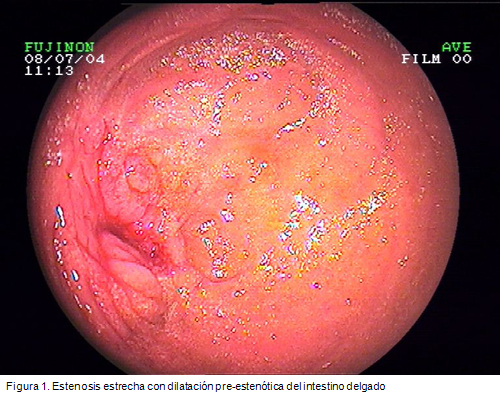

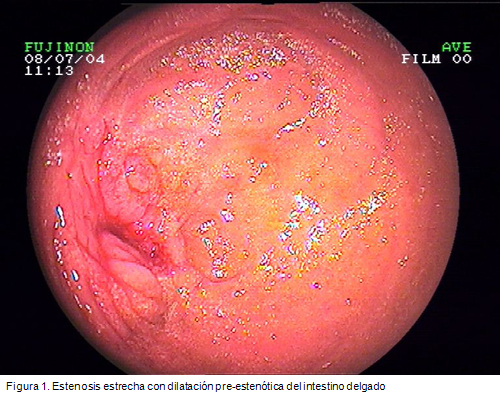

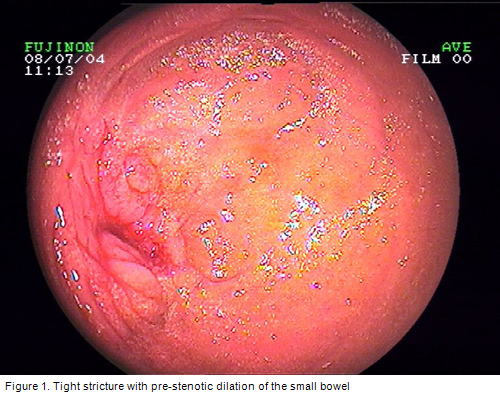

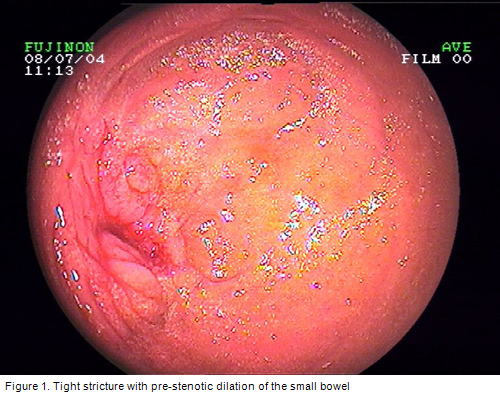

Durante un período de 5 años –desde 2004 a 2009– la paciente se presentó en total diez veces para dilataciones con balón por dos estenosis en el intestino delgado residual (Figura 1). En cada estadía se realizaron una a dos sesiones de dilatación por estenosis. Se eligió un balón de 8 a 18 mm de diámetro para el tratamiento, comenzando con 8 mm en la primera ocasión.

Además, durante una de las sesiones de endoscopia, se inyectó triamcinolona en las dos estenosis (inyección por cuadrantes, 40 mg en total por estenosis). Con esto no se logró modificar significativamente la evolución de la paciente.

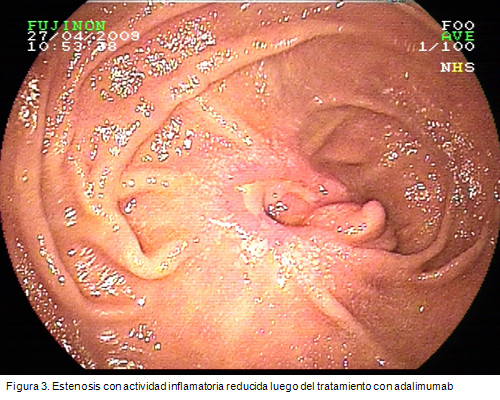

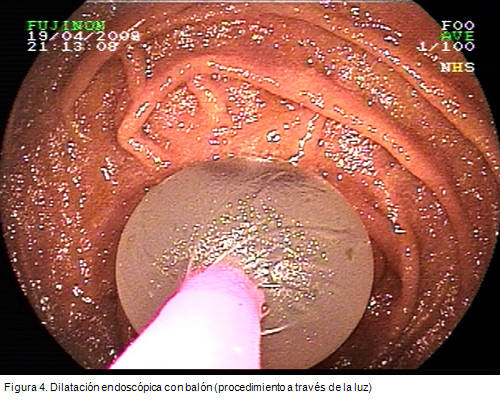

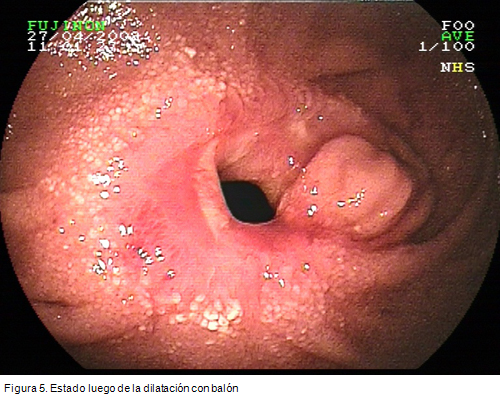

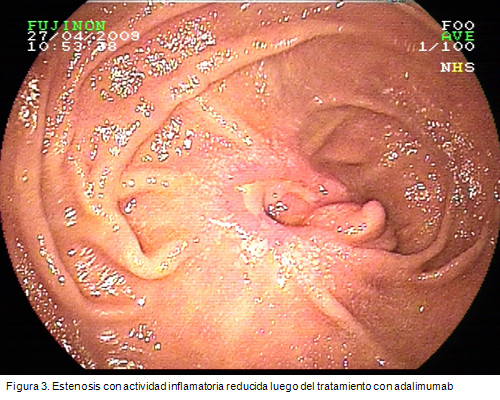

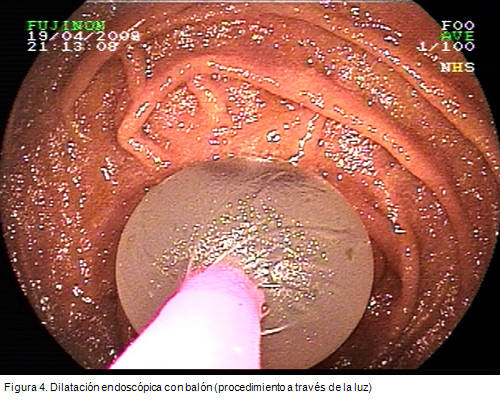

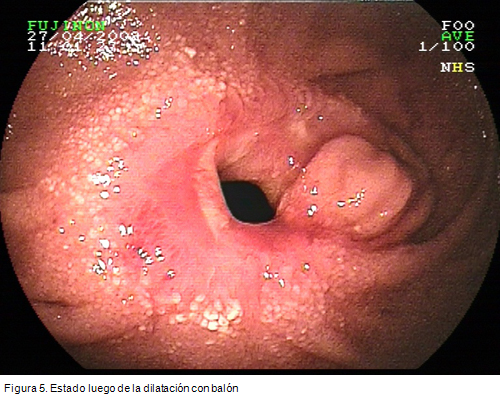

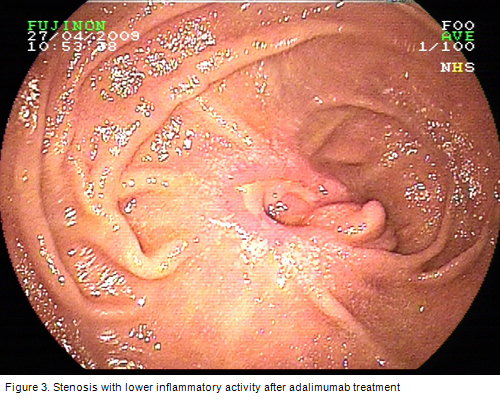

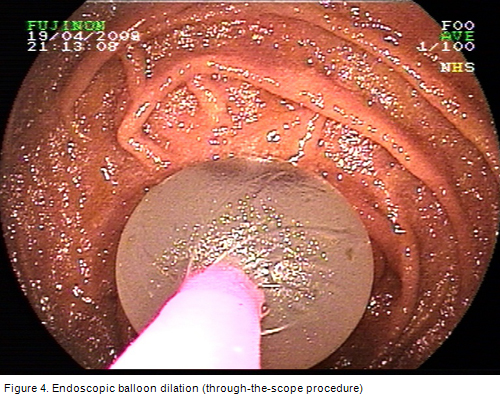

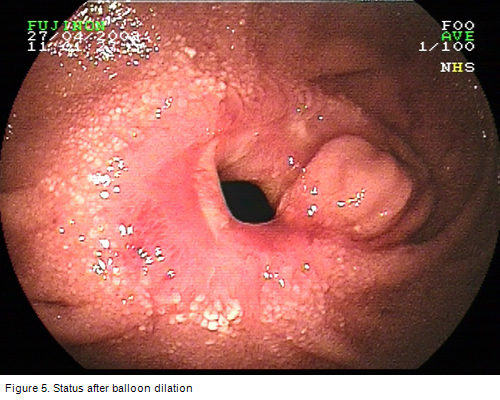

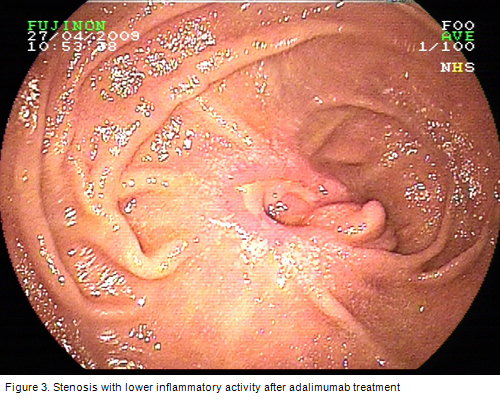

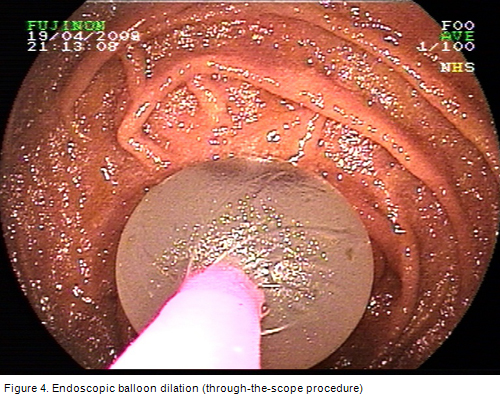

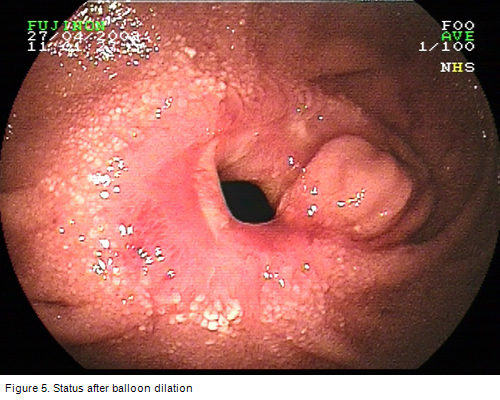

Luego de la dilatación de las dos estenosis a un diámetro máximo de 18 mm, y después de cambiar la medicación por adalimumab varios meses antes, el intervalo entre dos internaciones consecutivas pudo prolongarse hasta cuatro meses, y la paciente sólo tuvo síntomas obstructivos leves (Figuras 2 y 3). Endoscópicamente, la actividad inflamatoria en el área de la estenosis había disminuido. Nuevamente, se llevó a cabo una dilatación a 18 mm (Figuras 4 y 5) para aumentar el intervalo entre la presente y la próxima sesión de tratamiento.

Durante todo el período de cinco años nuestra paciente no requirió ningún procedimiento quirúrgico, como una estenoplastia.

Este caso demuestra la necesidad de un tratamiento interdisciplinario para las estenosis del intestino delgado secundarias a la enfermedad de Crohn. Las intervenciones quirúrgicas pueden evitarse con la elección de una estrategia terapéutica óptima (medicación y endoscopia) para cada paciente individual. No obstante, la dilatación endoscópica reiterada y un cambio en la medicación durante la evolución del paciente pueden ser necesarios para lograr una respuesta adecuada.

Discusión

La enteroscopia asistida por balón representa una herramienta de gran utilidad para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de las estenosis del intestino delgado en la EC. Con la dilatación endoscópica con balón puede evitarse la estenoplastia quirúrgica de las estenosis del intestino delgado. La tasa de éxito posible es de alrededor del 70%-80% y se compara con las tasas de éxito informadas con las dilataciones con balón utilizadas en la colonoscopia o en la enteroscopia de empuje.1,2 En contraste con la experiencia relativamente extensa con la endoscopia con doble balón (EDB),3,7,8 aún escasean los estudios sobre endoscopia con balón único (EBU). Además, la profundidad de la intubación lograda con la EBU puede ser menor en comparación con la EDB, especialmente en las áreas donde el intestino delgado está fijo, por ejemplo luego de cirugías abdominales previas o donde existen cambios por la cicatrización de procesos inflamatorios.

Por supuesto, no siempre necesitamos de los sistemas guiados por balón para el diagnóstico de EC en el intestino delgado profundo. En los casos de estenosis por EC conocidas o presuntas, la enteroscopia asistida por balón es considerada el método de elección para obtener la confirmación endoscópica e histológica. En la enfermedad de Crohn establecida, en pacientes con sospecha de actividad de la enfermedad en el intestino delgado y sin hallazgos significativos revelados por otras modalidades, la cápsula endoscópica puede considerarse en los pacientes sin sospecha de estenosis y la endoscopia por balón puede realizarse si no pueden descartarse las estenosis.4

Debe señalarse críticamente que en general se necesitan estudios con seguimientos más prolongados referidos a la dilatación de las estenosis del intestino delgado. Puede asumirse que una proporción sustancial de los pacientes podría requerir dilataciones terapéuticas reiteradas para lograr un alivio a largo plazo de los síntomas obstructivos. Aún no está claro cuál es la proporción de pacientes que pueden requerir estenoplastia quirúrgica pese al tratamiento médico y endoscópico intensivo en el largo plazo.

La elección de la medicación adecuada es un factor fundamental para lograr el éxito a largo plazo del tratamiento. En nuestra experiencia, el tratamiento con azatioprina generalmente es necesario para ello y para evitar el tratamiento reiterado o con altas dosis de corticoides en forma crónica.

En el caso informado, ni la medicación corticoidea ni la inyección de triamcinolona lograron el éxito a largo plazo del tratamiento. De hecho, un informe recientemente publicado9 señaló que el tratamiento solo con la inyección intraestenótica de triamcinolona puede no reducir el tiempo hasta la redilatación luego de la dilatación con balón de la estenosis de la EC, al menos en el área de anastomosis ileocolónicas.

En el paciente aquí presentado, los cambios inflamatorios en el área de dos estenosis disminuyeron después de la administración de adalimumab,10 y el intervalo entre sesiones consecutivas de tratamiento (dilatación con balón) pudo prolongarse. No obstante, el cambio de medicación puede no haber sido el único factor que influyó en el éxito del tratamiento en este paciente. Cuanto mayor el diámetro del balón elegido, mayor la posibilidad de éxito del tratamiento. Sin embargo, existe un riesgo relevante de perforación durante la dilatación con balón de las estenosis del intestino delgado. Se ha informado una tasa de perforación en la dilatación colonoscópica con balón de hasta el 10%. En nuestras series no se produjeron complicaciones.1 En la bibliografía, los diámetros del balón de hasta 25 mm se eligieron para el tratamiento endoscópico de las estenosis del intestino delgado en la EC. En el paciente descrito, seleccionamos no utilizar un diámetro mayor de 18 mm para evitar complicaciones, como la perforación o la hemorragia.

La experiencia europea

En 2007 hicimos un informe acerca del rendimiento diagnóstico y terapéutico de la EDB para estenosis sintomáticas en la enfermedad de Crohn (EC).1 Durante un período de tres años, desde 2003 a 2006, 19 pacientes con EC confirmada o presunta y estenosis sintomáticas del intestino delgado fueron sometidos a EDB y se incluyeron en nuestro análisis.1 Se evaluó al menos una estenosis de intestino delgado en cada paciente. En nueve de ellos, las estenosis no eran accesibles a la terapia endoscópica por razones anatómicas (3/9) o por actividad inflamatoria intensa dentro del segmento estenótico (6/9). Se les realizó tratamiento quirúrgico o inmunomodulador intensivo. En diez pacientes con 13 estenosis se realizaron 15 dilataciones durante la EDB. Se obtuvo el éxito técnico en ocho de los diez. Se logró alivio sintomático sin necesidad de cirugía en seis de los pacientes, que permanecieron asintomáticos durante un período de seguimiento promedio de diez meses (entre 4 y 16). No se observaron complicaciones en relación con la dilatación.

La experiencia japonesa

Sólo se publicaron algunos informes, fundamentalmente consistentes en pequeñas series de casos, acerca del uso de la EDB para el tratamiento de las estenosis del intestino delgado desde 2007. Fukumoto y col.,2 de Japón, intentaron identificar las características clínicas de las estenosis del intestino delgado. Otro objetivo del estudio fue determinar la validez de la dilatación con balón como una alternativa de tratamiento para estas estenosis. En un ensayo retrospectivo multicéntrico, se diagnosticaron estenosis en 179 pacientes de un total de 1 035 que se sometieron a EDB. Se hallaron lesiones en el intestino delgado en 156 pacientes. Lo más usual en los pacientes con estenosis del intestino delgado fue la enfermedad inflamatoria (n = 87) el íleon fue el sitio más frecuente de inflamación. La EC fue la más común entre las enfermedades inflamatorias. El éxito a largo plazo se obtuvo en 22 de los 31 pacientes que fueron sometidos a tratamiento de las estenosis con dilatación por balón.2

Generalidades de los sistemas de enteroscopia asistida por balón

Desde la introducción del sistema de la EDB (Fujinon, Inc., Saitama, Japón) en la endoscopia gastrointestinal en 2001,3 se han publicado diversos informes acerca del rendimiento diagnóstico y los resultados terapéuticos de este sistema. Para la endoscopia de intestino delgado existen dos enteroscopios de EDB disponibles 4. El EN-450P5 (tipo p) tiene un canal de trabajo de 2.2 mm, un diámetro externo de 8.5 mm, y un sobretubo de 12.2 mm de diámetro. El EN-450T5 (tipo t) tiene un canal de trabajo de 2.8 mm, un diámetro externo de 9.4 mm, y un sobretubo de 13.2 mm de diámetro. Recientemente, el sistema de enteroscopia de balón único (EBU) se introdujo a la endoscopia (Olympus, Tokio, Japón). El sistema EBU parece ser una versión “simplificada” del dispositivo de doble balón. El endoscopio (XSIF-Q160Y) consiste en un enteroscopio de alta resolución con una capacidad de trabajo para 200 cm.4,5 El dispositivo está equipado con un canal accesorio de 2.8 mm, y un sobretubo transparente con un balón libre de látex adherido a su extremo distal. En contraste con el dispositivo de EDB, no hay ningún balón adherido al enteroscopio, y por lo tanto la posición estable del dispositivo debe mantenerse anclando el extremo distal en la pared del intestino delgado o succionando la mucosa con la punta del enteroscopio. Si se considera necesario, el dispositivo Fujinon de EDB puede utilizarse también como EBU (no se incorpora el balón en el extremo distal del enteroscopio). Como ya se sabe con la EDB, la enteroscopia total es posible con la EBU. Hasta ahora, existen pocos estudios con EBU. En comparación con la EDB, la tasa de visualización completa del intestino delgado parece ser menor.5 Además, surge el interrogante de si ante alteraciones anatómicas, por ejemplo, estenosis en el área del intestino delgado o la existencia de segmentos fijos de intestino delgado posteriores a cirugías abdominales previas, puede lograrse una mayor profundidad de penetración con la EDB. La posibilidad de que haya un papel para el uso de un nuevo sistema como la enteroscopia espiral (Discovery SB Overtube; Spirus Medical, Stoughton, Massachusetts, EE.UU.)6 deberá ser demostrada en estudios futuros.

La enteroscopia guiada por balón no sólo ofrece la posibilidad del diagnóstico en el intestino delgado (incluyendo histología) y de terapéutica, por ejemplo, en las estenosis de la EC. La caracterización de la anatomía de la estenosis puede obtenerse mediante enteroclisis selectiva y puede excluirse la presencia de fístulas.

Las estrecheces fibroestenóticas de segmentos cortos en la EC sin una angulación o inflamación significativas son buenas candidatas para la dilatación con balón. Al usar endoscopios con un canal de trabajo de 2.8 mm (por ejemplo, EDB tipo t o EBU), un balón dilatador estándar puede ubicarse a través de la luz, y la dilatación por balón puede visualizarse bajo endoscopia. En contraste, al usar una EDB tipo p, la dilatación debe hacerse bajo guía fluoroscópica sobre un alambre a través del sobretubo luego de retirar el enteroscopio. Hasta ahora, no hay estudios que comparen la efectividad y la seguridad de ambas estrategias.

En conclusión, la enteroscopia con balón puede utilizarse en forma efectiva y segura para la dilatación de las estenosis del intestino delgado profundo. Hemos avanzado un gran paso en el tratamiento de las estenosis del intestino delgado en la enfermedad de Crohn. Se requieren más estudios con seguimientos más prolongados luego de la dilatación endoscópica con balón.

El autor no manifiesta conflictos de intereses.

La enfermedad de Crohn (EC) se complica frecuentemente con síntomas obstructivos secundarios a estenosis del intestino delgado. Estas estenosis usualmente no podían ser accesibles mediante la endoscopia convencional. Con el advenimiento de la enteroscopia de doble balón (EDB), ha sido posible no sólo realizar una evaluación diagnóstica de todo el intestino delgado, sino también la dilatación endoscópica con balón de las estenosis del intestino delgado.

En 2007 hicimos un informe acerca del rendimiento diagnóstico y terapéutico de la EDB, también conocida como enteroscopia de empuje y acortamiento (“push-and-pull enteroscopy”), para las estenosis sintomáticas del intestino delgado en la EC.1 Pudimos demostrar que la EDB es útil para el diagnóstico y para dirigir el tratamiento en los pacientes con estenosis del intestino delgado asociadas con la EC. La dilatación con balón durante la EDB demostró ser segura y efectiva. Por lo tanto puede considerarse como una alternativa a la cirugía en pacientes seleccionados con estenosis refractarias al tratamiento médico y con baja actividad inflamatoria en las estenosis.

Describimos el caso de una mujer de 47 años tratada repetidamente en nuestra unidad de endoscopia por estenosis del intestino delgado por enfermedad de Crohn. El caso ejemplifica la combinación de distintas estrategias para el tratamiento de las estenosis del intestino delgado.

Caso clínico

Cuando se presentó en nuestra unidad por primera vez, en 2004, la paciente tenía EC de 20 años de evolución. Se habían realizado varias resecciones de segmentos de intestino delgado debidas a estenosis con obstrucciones secundarias. Sólo quedaban aproximadamente 100 cm de intestino delgado residual. Durante tres años la paciente recibió tratamiento con corticoides (en forma intermitente) y azatioprina.

Durante un período de 5 años –desde 2004 a 2009– la paciente se presentó en total diez veces para dilataciones con balón por dos estenosis en el intestino delgado residual (Figura 1). En cada estadía se realizaron una a dos sesiones de dilatación por estenosis. Se eligió un balón de 8 a 18 mm de diámetro para el tratamiento, comenzando con 8 mm en la primera ocasión.

Además, durante una de las sesiones de endoscopia, se inyectó triamcinolona en las dos estenosis (inyección por cuadrantes, 40 mg en total por estenosis). Con esto no se logró modificar significativamente la evolución de la paciente.

Luego de la dilatación de las dos estenosis a un diámetro máximo de 18 mm, y después de cambiar la medicación por adalimumab varios meses antes, el intervalo entre dos internaciones consecutivas pudo prolongarse hasta cuatro meses, y la paciente sólo tuvo síntomas obstructivos leves (Figuras 2 y 3). Endoscópicamente, la actividad inflamatoria en el área de la estenosis había disminuido. Nuevamente, se llevó a cabo una dilatación a 18 mm (Figuras 4 y 5) para aumentar el intervalo entre la presente y la próxima sesión de tratamiento.

Durante todo el período de cinco años nuestra paciente no requirió ningún procedimiento quirúrgico, como una estenoplastia.

Este caso demuestra la necesidad de un tratamiento interdisciplinario para las estenosis del intestino delgado secundarias a la enfermedad de Crohn. Las intervenciones quirúrgicas pueden evitarse con la elección de una estrategia terapéutica óptima (medicación y endoscopia) para cada paciente individual. No obstante, la dilatación endoscópica reiterada y un cambio en la medicación durante la evolución del paciente pueden ser necesarios para lograr una respuesta adecuada.

Discusión

La enteroscopia asistida por balón representa una herramienta de gran utilidad para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de las estenosis del intestino delgado en la EC. Con la dilatación endoscópica con balón puede evitarse la estenoplastia quirúrgica de las estenosis del intestino delgado. La tasa de éxito posible es de alrededor del 70%-80% y se compara con las tasas de éxito informadas con las dilataciones con balón utilizadas en la colonoscopia o en la enteroscopia de empuje.1,2 En contraste con la experiencia relativamente extensa con la endoscopia con doble balón (EDB),3,7,8 aún escasean los estudios sobre endoscopia con balón único (EBU). Además, la profundidad de la intubación lograda con la EBU puede ser menor en comparación con la EDB, especialmente en las áreas donde el intestino delgado está fijo, por ejemplo luego de cirugías abdominales previas o donde existen cambios por la cicatrización de procesos inflamatorios.

Por supuesto, no siempre necesitamos de los sistemas guiados por balón para el diagnóstico de EC en el intestino delgado profundo. En los casos de estenosis por EC conocidas o presuntas, la enteroscopia asistida por balón es considerada el método de elección para obtener la confirmación endoscópica e histológica. En la enfermedad de Crohn establecida, en pacientes con sospecha de actividad de la enfermedad en el intestino delgado y sin hallazgos significativos revelados por otras modalidades, la cápsula endoscópica puede considerarse en los pacientes sin sospecha de estenosis y la endoscopia por balón puede realizarse si no pueden descartarse las estenosis.4

Debe señalarse críticamente que en general se necesitan estudios con seguimientos más prolongados referidos a la dilatación de las estenosis del intestino delgado. Puede asumirse que una proporción sustancial de los pacientes podría requerir dilataciones terapéuticas reiteradas para lograr un alivio a largo plazo de los síntomas obstructivos. Aún no está claro cuál es la proporción de pacientes que pueden requerir estenoplastia quirúrgica pese al tratamiento médico y endoscópico intensivo en el largo plazo.

La elección de la medicación adecuada es un factor fundamental para lograr el éxito a largo plazo del tratamiento. En nuestra experiencia, el tratamiento con azatioprina generalmente es necesario para ello y para evitar el tratamiento reiterado o con altas dosis de corticoides en forma crónica.

En el caso informado, ni la medicación corticoidea ni la inyección de triamcinolona lograron el éxito a largo plazo del tratamiento. De hecho, un informe recientemente publicado9 señaló que el tratamiento solo con la inyección intraestenótica de triamcinolona puede no reducir el tiempo hasta la redilatación luego de la dilatación con balón de la estenosis de la EC, al menos en el área de anastomosis ileocolónicas.

En el paciente aquí presentado, los cambios inflamatorios en el área de dos estenosis disminuyeron después de la administración de adalimumab,10 y el intervalo entre sesiones consecutivas de tratamiento (dilatación con balón) pudo prolongarse. No obstante, el cambio de medicación puede no haber sido el único factor que influyó en el éxito del tratamiento en este paciente. Cuanto mayor el diámetro del balón elegido, mayor la posibilidad de éxito del tratamiento. Sin embargo, existe un riesgo relevante de perforación durante la dilatación con balón de las estenosis del intestino delgado. Se ha informado una tasa de perforación en la dilatación colonoscópica con balón de hasta el 10%. En nuestras series no se produjeron complicaciones.1 En la bibliografía, los diámetros del balón de hasta 25 mm se eligieron para el tratamiento endoscópico de las estenosis del intestino delgado en la EC. En el paciente descrito, seleccionamos no utilizar un diámetro mayor de 18 mm para evitar complicaciones, como la perforación o la hemorragia.

La experiencia europea

En 2007 hicimos un informe acerca del rendimiento diagnóstico y terapéutico de la EDB para estenosis sintomáticas en la enfermedad de Crohn (EC).1 Durante un período de tres años, desde 2003 a 2006, 19 pacientes con EC confirmada o presunta y estenosis sintomáticas del intestino delgado fueron sometidos a EDB y se incluyeron en nuestro análisis.1 Se evaluó al menos una estenosis de intestino delgado en cada paciente. En nueve de ellos, las estenosis no eran accesibles a la terapia endoscópica por razones anatómicas (3/9) o por actividad inflamatoria intensa dentro del segmento estenótico (6/9). Se les realizó tratamiento quirúrgico o inmunomodulador intensivo. En diez pacientes con 13 estenosis se realizaron 15 dilataciones durante la EDB. Se obtuvo el éxito técnico en ocho de los diez. Se logró alivio sintomático sin necesidad de cirugía en seis de los pacientes, que permanecieron asintomáticos durante un período de seguimiento promedio de diez meses (entre 4 y 16). No se observaron complicaciones en relación con la dilatación.

La experiencia japonesa

Sólo se publicaron algunos informes, fundamentalmente consistentes en pequeñas series de casos, acerca del uso de la EDB para el tratamiento de las estenosis del intestino delgado desde 2007. Fukumoto y col.,2 de Japón, intentaron identificar las características clínicas de las estenosis del intestino delgado. Otro objetivo del estudio fue determinar la validez de la dilatación con balón como una alternativa de tratamiento para estas estenosis. En un ensayo retrospectivo multicéntrico, se diagnosticaron estenosis en 179 pacientes de un total de 1 035 que se sometieron a EDB. Se hallaron lesiones en el intestino delgado en 156 pacientes. Lo más usual en los pacientes con estenosis del intestino delgado fue la enfermedad inflamatoria (n = 87) el íleon fue el sitio más frecuente de inflamación. La EC fue la más común entre las enfermedades inflamatorias. El éxito a largo plazo se obtuvo en 22 de los 31 pacientes que fueron sometidos a tratamiento de las estenosis con dilatación por balón.2

Generalidades de los sistemas de enteroscopia asistida por balón

Desde la introducción del sistema de la EDB (Fujinon, Inc., Saitama, Japón) en la endoscopia gastrointestinal en 2001,3 se han publicado diversos informes acerca del rendimiento diagnóstico y los resultados terapéuticos de este sistema. Para la endoscopia de intestino delgado existen dos enteroscopios de EDB disponibles 4. El EN-450P5 (tipo p) tiene un canal de trabajo de 2.2 mm, un diámetro externo de 8.5 mm, y un sobretubo de 12.2 mm de diámetro. El EN-450T5 (tipo t) tiene un canal de trabajo de 2.8 mm, un diámetro externo de 9.4 mm, y un sobretubo de 13.2 mm de diámetro. Recientemente, el sistema de enteroscopia de balón único (EBU) se introdujo a la endoscopia (Olympus, Tokio, Japón). El sistema EBU parece ser una versión “simplificada” del dispositivo de doble balón. El endoscopio (XSIF-Q160Y) consiste en un enteroscopio de alta resolución con una capacidad de trabajo para 200 cm.4,5 El dispositivo está equipado con un canal accesorio de 2.8 mm, y un sobretubo transparente con un balón libre de látex adherido a su extremo distal. En contraste con el dispositivo de EDB, no hay ningún balón adherido al enteroscopio, y por lo tanto la posición estable del dispositivo debe mantenerse anclando el extremo distal en la pared del intestino delgado o succionando la mucosa con la punta del enteroscopio. Si se considera necesario, el dispositivo Fujinon de EDB puede utilizarse también como EBU (no se incorpora el balón en el extremo distal del enteroscopio). Como ya se sabe con la EDB, la enteroscopia total es posible con la EBU. Hasta ahora, existen pocos estudios con EBU. En comparación con la EDB, la tasa de visualización completa del intestino delgado parece ser menor.5 Además, surge el interrogante de si ante alteraciones anatómicas, por ejemplo, estenosis en el área del intestino delgado o la existencia de segmentos fijos de intestino delgado posteriores a cirugías abdominales previas, puede lograrse una mayor profundidad de penetración con la EDB. La posibilidad de que haya un papel para el uso de un nuevo sistema como la enteroscopia espiral (Discovery SB Overtube; Spirus Medical, Stoughton, Massachusetts, EE.UU.)6 deberá ser demostrada en estudios futuros.

La enteroscopia guiada por balón no sólo ofrece la posibilidad del diagnóstico en el intestino delgado (incluyendo histología) y de terapéutica, por ejemplo, en las estenosis de la EC. La caracterización de la anatomía de la estenosis puede obtenerse mediante enteroclisis selectiva y puede excluirse la presencia de fístulas.

Las estrecheces fibroestenóticas de segmentos cortos en la EC sin una angulación o inflamación significativas son buenas candidatas para la dilatación con balón. Al usar endoscopios con un canal de trabajo de 2.8 mm (por ejemplo, EDB tipo t o EBU), un balón dilatador estándar puede ubicarse a través de la luz, y la dilatación por balón puede visualizarse bajo endoscopia. En contraste, al usar una EDB tipo p, la dilatación debe hacerse bajo guía fluoroscópica sobre un alambre a través del sobretubo luego de retirar el enteroscopio. Hasta ahora, no hay estudios que comparen la efectividad y la seguridad de ambas estrategias.

En conclusión, la enteroscopia con balón puede utilizarse en forma efectiva y segura para la dilatación de las estenosis del intestino delgado profundo. Hemos avanzado un gran paso en el tratamiento de las estenosis del intestino delgado en la enfermedad de Crohn. Se requieren más estudios con seguimientos más prolongados luego de la dilatación endoscópica con balón.

El autor no manifiesta conflictos de intereses.

Balloon-assisted Enteroscopy for Small-Bowel Strictures in Crohn's Disease: Where are We Now?

(especial para SIIC © Derechos reservados)

(especial para SIIC © Derechos reservados)

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is frequently complicated by obstructive symptoms secondary to small-bowel strictures. These strictures could often not be accessed by conventional endoscopy. With the development of double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE), it became possible to perform not only a diagnostic work-up of the whole small bowel, but also endoscopic balloon dilation of small-bowel strictures.

In 2007, we reported on the diagnostic and therapeutic yield of DBE, which is also known as push-and-pull enteroscopy, for symptomatic small-bowel strictures in CD.1 We were able to show that DBE is useful for diagnosis and direction of therapy in patients with CD-associated strictures within the small bowel. Balloon dilation during DBE was shown to be safe and effective. It can therefore be considered as an alternative to surgery in selected patients with medically refractory strictures and low inflammatory activity of the strictures.

The aim of this article was to evaluate the current status regarding endoscopic dilation of small-bowel strictures in Crohn’s disease, including our own experience and future perspectives of small-bowel endoscopy.

Balloon-assisted enteroscopy for small-bowel strictures: Current status European experience

In 2007, we reported on the diagnostic and therapeutic yield of DBE for symptomatic small-bowel strictures in Crohn’s disease (CD).1 During a three-year period from 2003 to 2006, 19 patients with known or suspected CD and symptomatic small-bowel strictures were subjected to DBE and included in our analysis.1 At least one small-bowel stricture was assessed in each patient. In nine patients, strictures were not amenable to endoscopic therapy because of anatomical reasons (3/9) or severe inflammatory activity within the stenotic segment (6/9). They underwent direct surgery or intensified immunomodulatory treatment. In ten patients with 13 strictures, 15 dilations were performed during DBE. Technical success was achieved in eight of ten patients. Symptomatic relief with avoidance of surgery was achieved in six of the patients who remained symptom-free during a mean follow-up period of ten months (range 4-16). No dilation-associated complications were observed.

Japanese experience

Only few reports on the use of DBE for the therapeutic management of small-bowel strictures have been published since 2007, mainly consisting of small case series. Fukumoto et al.2 from Japan aimed to identify clinical features of small-bowel strictures. A further aim of the study was to determine the validity of balloon dilation as a treatment option for these strictures. In this retrospective multicenter trial, a total of 179 patients were identified to have strictures among a total 1 035 patients who underwent DBE. Lesions within the small bowel were found in 156 patients. Inflammatory disease (n = 87) was the most common in patients with small-bowel stricture, and the ileum was observed to be the most common site of inflammation. Crohn’s disease was the most common among the inflammatory diseases. Long-term success was achieved in 22 of the 31 patients who underwent balloon dilatation for stricture treatment.2

Overview of balloon-assisted enteroscopy systems

Since the introduction of the DBE system (Fujinon, Inc., Saitama, Japan) to gastrointestinal endoscopy in 2001,3 many reports have been published on the diagnostic yield and the therapeutic outcome of this system. For small-bowel enteroscopy, two different DBE enteroscopes are available.4 The EN-450P5 (p-type) has a working channel of 2.2 mm, an outer diameter of 8.5 mm, and an overtube with an outer diameter of 12.2 mm. The EN-450T5 (t-type) has a working channel of 2.8 mm, an outer diameter of 9.4 mm, and an overtube diameter of 13.2 mm. Recently, single-balloon enteroscopy (SBE) system was introduced to endoscopy (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The SBE system appears to be a “simplified” version of the double-balloon device. The endoscope (XSIF-Q160Y) consists of a high-resolution enteroscope with a working length of 200 cm.4,5 The device is equipped with a 2.8 mm accessory channel, and a transparent overtube with a latex-free balloon attached on its distal part. In contrast to the DBE device, there is no balloon attached to the enteroscope, and therefore stable position of the device has to be maintained by hooking the distal tip of the enteroscope into the small-bowel wall or by sucking of the mucosa with the tip of the endoscope. If deemed necessary, Fujinon DBE devices might also be used in a single-balloon technique (if the balloon is not mounted at the tip of the enteroscope). As it is already known from DBE, total enteroscopy is possible with SBE. Up to now, only a few studies have been made on SBE. When compared with DBE, the rate of whole small-bowel visualisation appears to be lower.5 Also, the question arises whether in anatomically altered situations, e.g. in the area of small-bowel strictures or when there are fixed small-bowel segments after previous abdominal surgery, a higher insertion depth may be achieved with the DBE system. Whether there might also a place for the use of new systems such as spiral enteroscopy (Discovery SB overtube; Spirus Medical, Stoughton, Massachusetts, USA)6 has to be proven in future studies.

Balloon-guided enteroscopy not only offers the possibility of small-bowel diagnosis (including histology) and therapy, e.g. in CD strictures. Characterization of the anatomy of a stricture can be obtained with selective enteroclysis, and the presence of fistulas can be excluded.

Technique

Short-segment fibrostenotic CD strictures without significant angulation or inflammation are good candidates for endoscopic balloon dilation. When using endoscopes having a working channel of 2.8 mm (e.g., t-type of DBE or SBE), a standard balloon dilator can be placed through the scope, and balloon dilation can be carried out under endoscopic view. In contrast, when using the p-type DB-enteroscope, the dilation has to be performed under fluoroscopic guidance over a wire through the overtube after removal of the enteroscope. Up to now, no studies comparing the effectiveness and safety of the two treatment approaches exist.

Own experience: case report

We describe the case of a 47-year old female patient repeatedly treated in our endoscopy unit because of small-bowel strictures deriving from Crohn’s disease. This case exemplifies the combination of the various approaches for the treatment of small-bowel strictures.

When presenting in our unit for the first time in 2004, the patient had a 20-year history of CD. Several small-bowel segment resections had been carried out because of strictures leading to intestinal obstruction. Only a total of approximately 100 cm of residual small bowel had been left in place. For three years, the patient had been under steroid medication (not continuously) and azathioprine.

During a 5-year period from 2004 to 2009, the patient presented a total of ten times for endoscopic balloon dilation of a total of two strictures in the residual small bowel (Figure 1). At each stay, one to two dilation sessions per stricture were carried out. A balloon diameter of 8-18 mm was chosen for the treatment, starting with 8 mm during the first presentation.

In addition, during one of the endoscopy sessions, triamcinolone was injected into the two strictures (local quadrantic injection, 40 mg total dose per stricture). By the latter approach, no significant change in the patient’s course could be achieved.

After dilation of the two stenoses to a maximum diameter of 18 mm, and after changing the medication to adalimumab several months before, the interval between two consecutive hospital stays could be prolonged to four months, and the patient had only slight obstruction symptoms. Endoscopically, the inflammatory activity in the area of the stenosis had decreased (Figures 2 and 3). Again, dilation to a diameter of 18 mm was carried out (Figures 4 and 5) in order to lengthen the interval between the present and the next treatment session.

During the whole period of five years, no new surgical intervention, such as stricturotomy, had to be carried out in our patient.

This case shows that an interdisciplinary approach to small-bowel strictures deriving from Crohn’s disease is required. Surgical interventions may be prevented by choosing the optimal treatment strategy (medication and endoscopy) for the individual patient. Nevertheless, repeated endoscopic dilation and change of medication during the patient’s course may be required in order to achieve an adequate response.

Where are we now?

Balloon-assisted enteroscopy represents a very useful tool for diagnosis and therapeutic management of small-bowel strictures in Crohn’s disease (CD). By carrying out endoscopic stricture dilation, surgical stricturotomy for small-bowel strictures may be avoided. The technical success rate achievable is about 70%-80% and compares to the technical success rates reported for balloon dilations using colonoscopy or push-enteroscopy.1,2 In contrast to the relatively large experience with double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE),3,7,8 studies on single-balloon enteroscopy (SBE) are still lacking. Also, the intubation depth achieved by SBE may be lower compared with DBE, especially in areas where the small bowel is fixed, e.g. after previous abdominal surgery, or where there are scarry changes after healing of inflammatory processes.

Of course, we do not always need balloon-guided systems for diagnosis of CD of the deep small bowel. In cases of known or suspected CD stricture, balloon-assisted enteroscopy is considered the method of choice to obtain endoscopic and histological confirmation. In established Crohn’s disease, for patients in whom small-bowel disease activity is suspected, and significant findings have not been revealed by other modalities, capsule endoscopy can be considered in patients without suspected stenosis, and balloon enteroscopy may be performed if strictures cannot be ruled out.4

It has to be critically remarked that in general a longer follow-up for studies dealing with endoscopic dilation of small-bowel strictures is required. It can be assumed that a substantial rate of patients may require repeated dilation therapy in order to achieve long-term freedom from obstruction symptoms. It remains unclear which proportion of patients may require surgical stricturotomy despite intensified medical and endoscopic treatment in the long run.

Choosing the right medication is a key factor for achievement of long-term treatment success. In our experience, azathioprine treatment is often necessary in order to assure long-term success and to avoid repeated or long-term treatment with high-dose steroids.

In the case reported, neither steroid medication nor local triamcinolone injection led to long-term success of treatment. In fact, a recently published report9 has shown that single treatment of intrastricture triamcinolone injection may not reduce the time to redilatation after balloon dilatation of Crohn's strictures, at least in the area of ileocolonic anastomoses.

In the patient presently reported, inflammatory changes in the area of the two stenoses decreased after administration of adalimumab,10 and the interval between consecutive treatment sessions (balloon dilation) could be lengthened. Nevertheless, the change of medication may not have been the only factor influencing the treatment success in our patient reported. The larger the balloon diameter chosen, the better the treatment success may be. Nevertheless, there is a relevant risk of perforation during balloon dilation of small-bowel strictures. The perforation rate of colonoscopic balloon dilation has been reported to be up to 10%. In our own series, no complications occurred.1

In the literature, balloon diameters of up to 25 mm were chosen for the endoscopic treatment of CD small-bowel stenoses. In the patient reported, we have chosen not to go beyond a diameter of 18 mm in order to avoid complications, such as perforation or bleeding.

In conclusion, balloon-guided enteroscopy can be used effectively and safely for stricture dilation in the deep small bowel. We have taken a big step forward in the treatment of small-bowel strictures in Crohn’s disease. Further studies including a longer follow-up after endoscopic balloon dilation are required.

Crohn’s disease (CD) is frequently complicated by obstructive symptoms secondary to small-bowel strictures. These strictures could often not be accessed by conventional endoscopy. With the development of double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE), it became possible to perform not only a diagnostic work-up of the whole small bowel, but also endoscopic balloon dilation of small-bowel strictures.

In 2007, we reported on the diagnostic and therapeutic yield of DBE, which is also known as push-and-pull enteroscopy, for symptomatic small-bowel strictures in CD.1 We were able to show that DBE is useful for diagnosis and direction of therapy in patients with CD-associated strictures within the small bowel. Balloon dilation during DBE was shown to be safe and effective. It can therefore be considered as an alternative to surgery in selected patients with medically refractory strictures and low inflammatory activity of the strictures.

The aim of this article was to evaluate the current status regarding endoscopic dilation of small-bowel strictures in Crohn’s disease, including our own experience and future perspectives of small-bowel endoscopy.

Balloon-assisted enteroscopy for small-bowel strictures: Current status European experience

In 2007, we reported on the diagnostic and therapeutic yield of DBE for symptomatic small-bowel strictures in Crohn’s disease (CD).1 During a three-year period from 2003 to 2006, 19 patients with known or suspected CD and symptomatic small-bowel strictures were subjected to DBE and included in our analysis.1 At least one small-bowel stricture was assessed in each patient. In nine patients, strictures were not amenable to endoscopic therapy because of anatomical reasons (3/9) or severe inflammatory activity within the stenotic segment (6/9). They underwent direct surgery or intensified immunomodulatory treatment. In ten patients with 13 strictures, 15 dilations were performed during DBE. Technical success was achieved in eight of ten patients. Symptomatic relief with avoidance of surgery was achieved in six of the patients who remained symptom-free during a mean follow-up period of ten months (range 4-16). No dilation-associated complications were observed.

Japanese experience

Only few reports on the use of DBE for the therapeutic management of small-bowel strictures have been published since 2007, mainly consisting of small case series. Fukumoto et al.2 from Japan aimed to identify clinical features of small-bowel strictures. A further aim of the study was to determine the validity of balloon dilation as a treatment option for these strictures. In this retrospective multicenter trial, a total of 179 patients were identified to have strictures among a total 1 035 patients who underwent DBE. Lesions within the small bowel were found in 156 patients. Inflammatory disease (n = 87) was the most common in patients with small-bowel stricture, and the ileum was observed to be the most common site of inflammation. Crohn’s disease was the most common among the inflammatory diseases. Long-term success was achieved in 22 of the 31 patients who underwent balloon dilatation for stricture treatment.2

Overview of balloon-assisted enteroscopy systems

Since the introduction of the DBE system (Fujinon, Inc., Saitama, Japan) to gastrointestinal endoscopy in 2001,3 many reports have been published on the diagnostic yield and the therapeutic outcome of this system. For small-bowel enteroscopy, two different DBE enteroscopes are available.4 The EN-450P5 (p-type) has a working channel of 2.2 mm, an outer diameter of 8.5 mm, and an overtube with an outer diameter of 12.2 mm. The EN-450T5 (t-type) has a working channel of 2.8 mm, an outer diameter of 9.4 mm, and an overtube diameter of 13.2 mm. Recently, single-balloon enteroscopy (SBE) system was introduced to endoscopy (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The SBE system appears to be a “simplified” version of the double-balloon device. The endoscope (XSIF-Q160Y) consists of a high-resolution enteroscope with a working length of 200 cm.4,5 The device is equipped with a 2.8 mm accessory channel, and a transparent overtube with a latex-free balloon attached on its distal part. In contrast to the DBE device, there is no balloon attached to the enteroscope, and therefore stable position of the device has to be maintained by hooking the distal tip of the enteroscope into the small-bowel wall or by sucking of the mucosa with the tip of the endoscope. If deemed necessary, Fujinon DBE devices might also be used in a single-balloon technique (if the balloon is not mounted at the tip of the enteroscope). As it is already known from DBE, total enteroscopy is possible with SBE. Up to now, only a few studies have been made on SBE. When compared with DBE, the rate of whole small-bowel visualisation appears to be lower.5 Also, the question arises whether in anatomically altered situations, e.g. in the area of small-bowel strictures or when there are fixed small-bowel segments after previous abdominal surgery, a higher insertion depth may be achieved with the DBE system. Whether there might also a place for the use of new systems such as spiral enteroscopy (Discovery SB overtube; Spirus Medical, Stoughton, Massachusetts, USA)6 has to be proven in future studies.

Balloon-guided enteroscopy not only offers the possibility of small-bowel diagnosis (including histology) and therapy, e.g. in CD strictures. Characterization of the anatomy of a stricture can be obtained with selective enteroclysis, and the presence of fistulas can be excluded.

Technique

Short-segment fibrostenotic CD strictures without significant angulation or inflammation are good candidates for endoscopic balloon dilation. When using endoscopes having a working channel of 2.8 mm (e.g., t-type of DBE or SBE), a standard balloon dilator can be placed through the scope, and balloon dilation can be carried out under endoscopic view. In contrast, when using the p-type DB-enteroscope, the dilation has to be performed under fluoroscopic guidance over a wire through the overtube after removal of the enteroscope. Up to now, no studies comparing the effectiveness and safety of the two treatment approaches exist.

Own experience: case report

We describe the case of a 47-year old female patient repeatedly treated in our endoscopy unit because of small-bowel strictures deriving from Crohn’s disease. This case exemplifies the combination of the various approaches for the treatment of small-bowel strictures.

When presenting in our unit for the first time in 2004, the patient had a 20-year history of CD. Several small-bowel segment resections had been carried out because of strictures leading to intestinal obstruction. Only a total of approximately 100 cm of residual small bowel had been left in place. For three years, the patient had been under steroid medication (not continuously) and azathioprine.

During a 5-year period from 2004 to 2009, the patient presented a total of ten times for endoscopic balloon dilation of a total of two strictures in the residual small bowel (Figure 1). At each stay, one to two dilation sessions per stricture were carried out. A balloon diameter of 8-18 mm was chosen for the treatment, starting with 8 mm during the first presentation.

In addition, during one of the endoscopy sessions, triamcinolone was injected into the two strictures (local quadrantic injection, 40 mg total dose per stricture). By the latter approach, no significant change in the patient’s course could be achieved.

After dilation of the two stenoses to a maximum diameter of 18 mm, and after changing the medication to adalimumab several months before, the interval between two consecutive hospital stays could be prolonged to four months, and the patient had only slight obstruction symptoms. Endoscopically, the inflammatory activity in the area of the stenosis had decreased (Figures 2 and 3). Again, dilation to a diameter of 18 mm was carried out (Figures 4 and 5) in order to lengthen the interval between the present and the next treatment session.

During the whole period of five years, no new surgical intervention, such as stricturotomy, had to be carried out in our patient.

This case shows that an interdisciplinary approach to small-bowel strictures deriving from Crohn’s disease is required. Surgical interventions may be prevented by choosing the optimal treatment strategy (medication and endoscopy) for the individual patient. Nevertheless, repeated endoscopic dilation and change of medication during the patient’s course may be required in order to achieve an adequate response.

Where are we now?

Balloon-assisted enteroscopy represents a very useful tool for diagnosis and therapeutic management of small-bowel strictures in Crohn’s disease (CD). By carrying out endoscopic stricture dilation, surgical stricturotomy for small-bowel strictures may be avoided. The technical success rate achievable is about 70%-80% and compares to the technical success rates reported for balloon dilations using colonoscopy or push-enteroscopy.1,2 In contrast to the relatively large experience with double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE),3,7,8 studies on single-balloon enteroscopy (SBE) are still lacking. Also, the intubation depth achieved by SBE may be lower compared with DBE, especially in areas where the small bowel is fixed, e.g. after previous abdominal surgery, or where there are scarry changes after healing of inflammatory processes.

Of course, we do not always need balloon-guided systems for diagnosis of CD of the deep small bowel. In cases of known or suspected CD stricture, balloon-assisted enteroscopy is considered the method of choice to obtain endoscopic and histological confirmation. In established Crohn’s disease, for patients in whom small-bowel disease activity is suspected, and significant findings have not been revealed by other modalities, capsule endoscopy can be considered in patients without suspected stenosis, and balloon enteroscopy may be performed if strictures cannot be ruled out.4

It has to be critically remarked that in general a longer follow-up for studies dealing with endoscopic dilation of small-bowel strictures is required. It can be assumed that a substantial rate of patients may require repeated dilation therapy in order to achieve long-term freedom from obstruction symptoms. It remains unclear which proportion of patients may require surgical stricturotomy despite intensified medical and endoscopic treatment in the long run.

Choosing the right medication is a key factor for achievement of long-term treatment success. In our experience, azathioprine treatment is often necessary in order to assure long-term success and to avoid repeated or long-term treatment with high-dose steroids.

In the case reported, neither steroid medication nor local triamcinolone injection led to long-term success of treatment. In fact, a recently published report9 has shown that single treatment of intrastricture triamcinolone injection may not reduce the time to redilatation after balloon dilatation of Crohn's strictures, at least in the area of ileocolonic anastomoses.

In the patient presently reported, inflammatory changes in the area of the two stenoses decreased after administration of adalimumab,10 and the interval between consecutive treatment sessions (balloon dilation) could be lengthened. Nevertheless, the change of medication may not have been the only factor influencing the treatment success in our patient reported. The larger the balloon diameter chosen, the better the treatment success may be. Nevertheless, there is a relevant risk of perforation during balloon dilation of small-bowel strictures. The perforation rate of colonoscopic balloon dilation has been reported to be up to 10%. In our own series, no complications occurred.1

In the literature, balloon diameters of up to 25 mm were chosen for the endoscopic treatment of CD small-bowel stenoses. In the patient reported, we have chosen not to go beyond a diameter of 18 mm in order to avoid complications, such as perforation or bleeding.

In conclusion, balloon-guided enteroscopy can be used effectively and safely for stricture dilation in the deep small bowel. We have taken a big step forward in the treatment of small-bowel strictures in Crohn’s disease. Further studies including a longer follow-up after endoscopic balloon dilation are required.

Hendrik Manner, HSK Wiesbaden Department of Internal Medicine II, 65199, Wiesbaden, Alemania,

e-mail: HSManner@gmx.de

1. Pohl J, May A, Nachbar L, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic yield of push-and-pull enteroscopy for symptomatic small bowel Crohn's disease strictures. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 19(7):529-34, 2007.

2. Fukumoto A, Tanaka S, Yamamoto H, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel stricture by double balloon endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 66(3 Suppl):S108-12, 2007.

3. Yamamoto H, Sekine Y, Sato Y, Higashizawa T, Miyata T, Lino S et al. Total enteroscopy with a nonsurgical steerable double-balloon method. Gastrointest Endosc 53:216-220, 2001.

4. Pohl J, Delvaux M, Ell C, et al. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guidelines: flexible enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel diseases. Endoscopy 40(7):609-18, 2008.

5. Kawamura T, Yasuda K, Tanaka K, et al. Clinical evaluation of a newly developed single-balloon enteroscope. Gastrointest Endosc 68(6):1112-6, 2008.

6. Buscaglia JM, Dunbar KB, Okolo PI 3rd, et al. The spiral enteroscopy training initiative: results of a prospective study evaluating the Discovery SB overtube device during small bowel enteroscopy (with video). Endoscopy 41(3):194-9, 2009.

7. Ell C, May A, Nachbar L, Cellier C, Landi B, Di Caro S et al. Push-and-pull enteroscopy in the small bowel using the double-balloon technique: results of a prospective European multicenter study. Endoscopy 37:613-616, 2005.

8. May A, Nachbar L, Ell C. Double balloon enteroscopy (push-and-pull enteroscopy) for the small bowel: feasibility and diagnostic and therapeutic yield in patients with suspected small bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc 62:62-70, 2005.

9. East JE, Brooker JC, Rutter MD, Saunders BP. A pilot study of intrastricture steroid versus placebo injection after balloon dilatation of Crohn's strictures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 5(9):1065-9, 2007.

10. Feagan BG, Panaccione R, Sandborn WJ, et al. Effects of adalimumab therapy on incidence of hospitalization and surgery in Crohn's disease: results from the CHARM study. Gastroenterology 135(5):1493-9, 2008.

Está expresamente prohibida la redistribución y la redifusión de todo o parte de los

contenidos de la Sociedad Iberoamericana de Información Científica (SIIC) S.A. sin

previo y expreso consentimiento de SIIC.

ua91218