Casos Clínicos

PRESENTACION MANDIBULAR PRIMARIA DEL LINFOMA NO HODGKIN

Los linfomas no Hodgkin comprenden un grupo de neoplasias con un amplio espectro de comportamiento. Cuando se presentan en la mandíbula pueden aparentar ser infecciones odontogénicas o tumores benignos. Los autores comentan un caso clínico y resumen los conocimientos actuales sobre esta enfermedad.

Coautores

Karthikeya Patil* Prasannasrinivas Deshpande**

J.S.S Dental College and Hospital, Mysore, India*

BDS, (MDS), J.S.S Dental College and Hospital, Mysore, India**

Karthikeya Patil* Prasannasrinivas Deshpande**

J.S.S Dental College and Hospital, Mysore, India*

BDS, (MDS), J.S.S Dental College and Hospital, Mysore, India**

Clasificación en siicsalud

Artículos originales > Expertos del Mundo >

página /dato/casiic.php/121127

Especialidades

Artículos originales > Expertos del Mundo >

página /dato/casiic.php/121127

Especialidades

Primera edición en siicsalud

3 de octubre, 2011

3 de octubre, 2011

Introducción

Los linfomas sonun grupo deneoplasiasmalignasque afectan alsistema linforreticular.1Estas neoplasiashan sido tradicionalmentedivididas entipo Hodgkin ytipo no Hodgkin, ypuede surgir de laslíneas celulares linfocíticas B o T.La mayoría delos linfomasno Hodgkin(LNH) se presentanen los ganglios linfáticos, aunque en raras ocasiones pueden existirsitios primarios extranodales.La localización mandibular primariaes inclusomásrara.2

Caso clínico

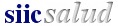

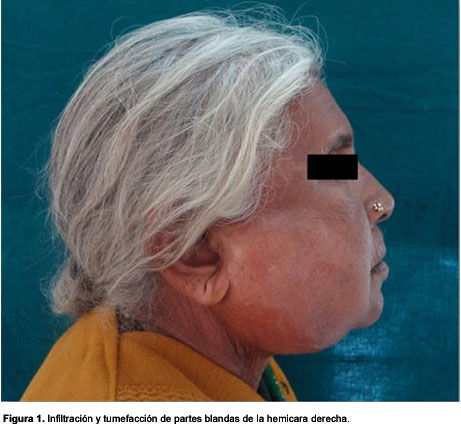

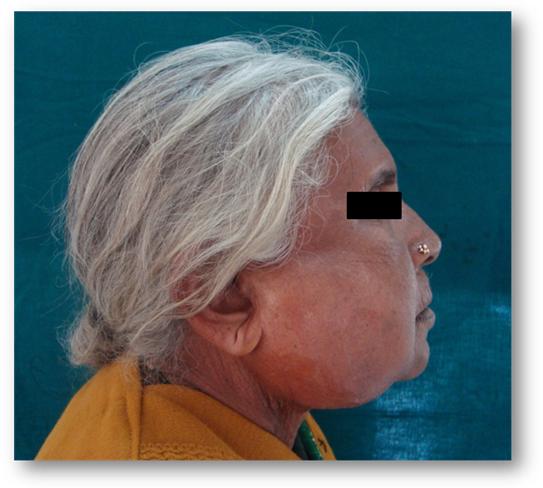

Se presenta una paciente de sexo femenino deochenta añoscon unatumoraciónde rápido crecimientoen el ladoderecho de la carade 20días de evolución.La tumoración había aparecido de manera repentina,era moderadamentedolorosay no había respondidoa las terapias convencionales.La paciente tenía la sensibilidadalterada enla región comprometiday dificultad paraabrir la boca.No presentó manifestaciones sistémicascomo fiebreo pérdida de peso.Los antecedentes personales y médicos delapaciente no contribuían para esclarecer el diagnóstico.

El examen clínico revelóuna grantumoraciónextraoraldifusa enla parte central derechay en el tercio inferiorde la cara.Esta tumoración parecíatensa,sincambios secundarios.Había unaumentolocal de la temperaturay dolora la palpación.El tumor erade consistencia firmeynofluctuante.No se pudieron examinar los ganglios linfáticos regionalesdebido a lagran hinchazón.El examen de la región intraoralreveló una inflamación difusadela mucosa bucal del lado derecho, del vestíbuloy de la regiónretromolar.Los dientespróximos a la región inflamada estaban moderadamente cariados y móviles, por lo cual sehabía diagnosticado clínicamente una infección del espacio odontogénico.

Sin embargo, larapidez de la progresión de la lesión,su naturalezasobredimensionada ysufalta de respuestaa los tratamientos convencionaleshicieron pensar en una entidadagresiva, probablementeuntumor maligno,y alentaronuna investigación más profunda.

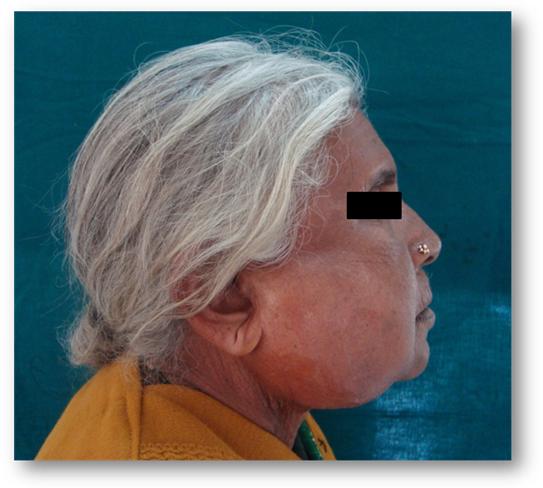

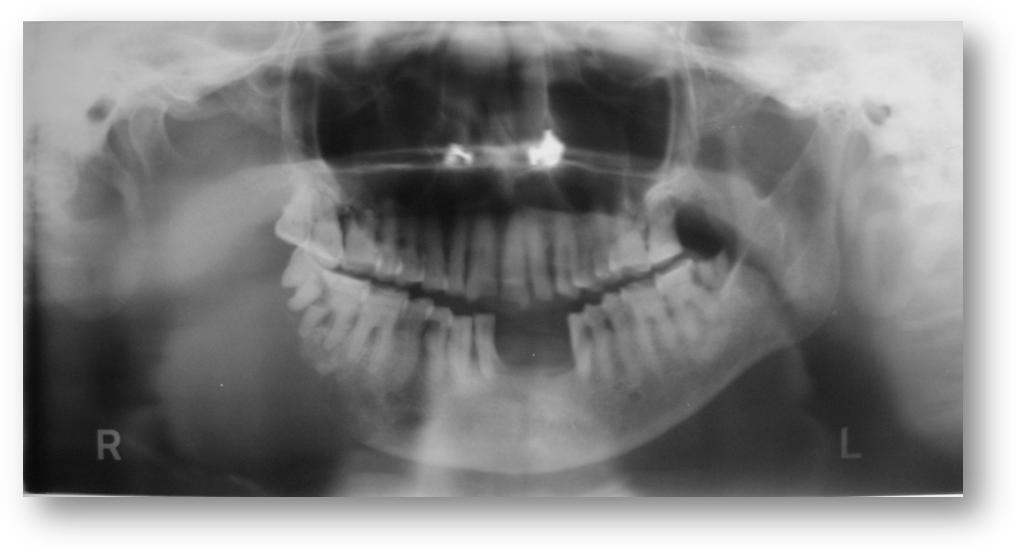

Una radiografía panorámicamostró una lesiónosteolíticairregularmasiva que ocupaba todo el cuerpo de la mandíbulay su ramaderecha hastael cóndilo mandibular.La tomografía computarizadaconfirmólos hallazgos radiológicos.Los resultados de los exámenes hematológicosse encontrabandentro de los límites normales.

Por medio de una citologíaaspirativa con aguja finase detectaroncélulas linfoides atípicasgrandesen un fondo deeosinófilos dispersos.Una biopsia incisionalmostrócapas difusas decélulas linfoidescon grandesnúcleos vesicularesy nucléolos prominentes.Se encontraron indicios deaumento dela actividad mitóticay áreas de necrosis.Enel análisis inmunohistoquímico, las células tumoralesfueron positivas de forma difusa para elantígeno leucocitario común (CD45).Se llegó al diagnóstico final delinfoma difusode células grandes tipo B (LDCGB). La búsqueda de metástasisno reveló lesiones secundarias.

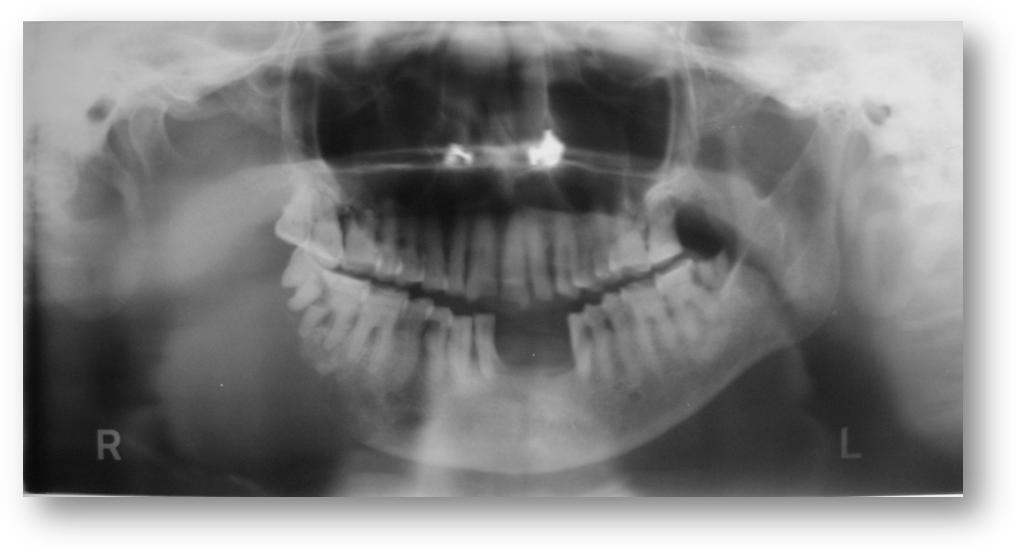

La paciente fue derivadaa uncentro oncológicoregional, donde realizó seisciclos completos delrégimen estándardequimioterapia CHOP (ciclofosfamida, doxorrubicina, vincristina y prednisona).Al finalizar eltercer ciclode quimioterapia ya se observaba una resolución casi completadel tumor.

Discusión

Los LNH involucran principalmente los ganglios linfáticos.Sin embargo, hasta el 40% de ellos pueden presentarse en forma primaria en sitios extranodales.3-6 La afectación de la cabeza y el cuello es rara y los sitios comunes de aparición son el anillo de Waldeyer, el piso de la boca, las glándulas salivales, la mucosa bucal, los senos paranasales y el hueso.2,7La cavidad oral solamente está involucrada en alrededor del 0.1% al 5% de los casos.4,8,9

La etiología exacta de los linfomas es desconocida.En su aparición han sido implicados la predisposición genética, los estados de inmunodeficiencia como los que padecen los infectados por VIH o los receptores de trasplantes y la translocación cromosómica.1

Descritos por primera vez por Parker y Jackson (1939), los linfomas óseos son poco frecuentes y representan sólo el 5% de todos los LNH extranodales.10Estos linfomas se originan en la cavidad medular del hueso, sin afectar los ganglios linfáticos regionales ni los órganos viscerales por un período de seis meses.11,12Estos tumores son histológicamente similares a los linfomas primarios nodales.13En la región cráneo-facial, los maxilares son un sitio frecuente de aparición de linfomas óseos, y el maxilar superior se ve comprometido con mayor frecuencia que la mandíbula.10,14,15

Los linfomas óseos aparecen en individuos de un amplio rango etario, que comprende desde el primer año de vida hasta los 86 años.2,16Son raros en lactantes y niños, y tienen una tendencia a presentarse en adultos mayores.La distribución por sexo es variable; diversos estudios indican que la relación hombres:mujeres va desde 1.5:117 a 5:118.También se ha observado una relación inversa de 1:3 en otro estudio2.El presente caso constituye una de las presentaciones raras del LNH que afecta al hueso en forma primaria, sin comprometer los ganglios linfáticos ni los órganos viscerales, en una paciente de sexo femenino de 80 años de edad.

Clínicamente, los linfomas de la mandíbula se presentan como una inflamación local con un dolor sordo o constante en los huesos.2Dentro de la boca, se pueden presentar como una masa palpable en las partes blandas.Otros signos y síntomas incluyen dolor dental inexplicable y persistente o movilidad dentaria, parestesia o entumecimiento, la presencia de una masa en las encías o en la concavidad consecutiva a una extracción, ulceraciones persistentes y cambios osteolíticos mal definidos en las radiografías.10,19-27La mayoría de estas características simulan ser alteraciones comunes inflamatorias o benignas de la cavidad oral y pueden ser desorientadoras, como sucedió en el caso actual. El profesional de la salud debe estar alerta y observar estas características con precaución para evitar realizar un diagnóstico más convencional y perder tiempo valioso para el paciente con tratamientos inadecuados.

En la actualidad se utiliza la clasificación de Ann Arbor para la estadificación clínica de los LNH.28Nuestra paciente fue ubicada en el estadio IE A, es decir, compromiso de un único órgano o sitio extranodal, sin síntomas sistémicos.

Alrededor del 80% de los LNH presentan cambios osteolíticos erosivos en las radiografías.Otros tienen una apariencia radiográfica esclerótica o mixta. A veces se pueden observar grandes masas de tejidos blandos extraóseos con destrucción cortical mínima en las radiografías simples.29

En las radiografías panorámicas e intraorales se puede observar específicamente pérdida de la definición cortical del canal dentario inferior, ensanchamiento del canal dentario y del foramen mentoniano, pérdida de la lámina dura y ensanchamiento del espacio del ligamento periodontal.22,30,31Las imágenes por tomografía computarizada (TC) y resonancia magnética nuclear ayudan a visualizar con claridad estos cambios, así como el patrón de destrucción ósea trabecular y el reemplazo de la médula ósea, que generalmente son característicos de los tumores agresivos.32Nuestra paciente presentaba una lesión osteolítica extensa que involucraba casi toda la rama derecha de la mandíbula y se extendía hasta comprometer una parte del cuerpo mandibular.Las imágenes por TC de la lesión nos ayudaron a delinear la lesión en forma neta y a visualizar claramente la arquitectura interna.El aspecto radiográfico tan agresivo nos orientó hacia una enfermedad más grave.

La mayoría de los linfomas se originan en las células de la línea B.El LDCGB representa aproximadamente el 40% de todos los linfomas de células B33 y suele ser agresivo.28Puede aparecer en los ganglios linfáticos o en sitios extranodales y puede causar una destrucción extensa de los huesos afectados.Alrededor del 50% de estos linfomas se diagnostican en el estadio I o II.28,34

Histológicamente, los LDCGB se presentan con capas de grandes células linfoides con núcleos de gran tamaño, que en algunos casos pueden ser escindidas.En algunas lesiones se puede observar un abundante citoplasma, que es pálido o basófilo y la formación de centros germinales.35Los LDCGB se han clasificado de acuerdo con su pronóstico sobre la base de la formación de centros germinales como “similar a centro germinal de células B” (CGB) y “no similar a centro germinal de células B” (no-CGB).Un estudio demostró que el LDCGB oral primario pertenece principalmente al grupo de los no-CGB y presenta un pronóstico más grave en comparación con el grupo de linfomas GCB.36 El antígeno leucocitario común (CD45) es positivo en más del 95% de los casos.37

En la década de 1980, los linfomas fueron clasificados como de bajo grado, de grado intermedio y de alto grado, pero con varias limitaciones.A principios de la década de 1990 se propuso la clasificación REAL, la cual fue aceptada por la OMS luego de sufrir algunas modificaciones de menor importancia.Esta clasificación se basa únicamente en las características histopatológicas e inmunohistoquímicas.1

El diagnóstico de los linfomas óseos se basa en los hallazgos clínicos, radiológicos e histopatológicos.Las exploraciones abdominales, los escaneos PET, los análisis de laboratorio como hemograma completo, lactato deshidrogenasa, análisis de orina, la biopsia aspirativa de médula ósea y las técnicas avanzadas de inmunohistoquímica desempeñan un papel importante en la búsqueda y la obtención de un diagnóstico de certeza.2

En el caso actual, las características histológicas, la inmunohistoquímica y los hallazgos clínicos y radiológicos acentuados fueron de gran valor para llegar al diagnóstico, aunque otras investigaciones no revelaban anormalidades.

La quimioterapia y la radioterapia, utilizadas solas o combinadas, son las principales estrategias de tratamiento.2La terapia combinada proporciona un resultado superior en comparación con la monoterapia.38,39La quimioterapia estándar incluye el régimen CHOP.En los últimos tiempos se ha recomendado emplear la variante RCHOP, es decir, la combinación del régimen CHOP con rituximab (un anticuerpo quimérico anti-CD20).34La radioterapia en el intervalo de 2 400 a 5 600 cGy (35-40 Gy) administrada en fracciones diarias de 180 cGy también ha demostrado ser eficaz.38

El linfoma primario de hueso tiene un pronóstico excelente, más aún en el estadio I y con el uso de la terapia combinada.2,33La tasa de supervivencia a 5 años oscila entre el 50% y el 90%, de acuerdo con los factores pronósticos.33,34,38La tasa de supervivencia a 5 años para los pacientes que presentan estos linfomas en la región maxilofacial es de aproximadamente el 50%.2En el presente caso se logró una excelente respuesta solamente con el régimen de quimioterapia CHOP.La paciente se encuentra en seguimiento y no ha presentado recurrencias hasta la fecha.

Conclusiones

Las formas inespecíficas de presentación de los LNH extranodales de cabeza y cuello, especialmente las que comprometen los maxilares, pueden ser erróneamente interpretadas como otras alteraciones dentarias comunes con cierta frecuencia.Una mayor comprensión de la enfermedad, un diagnóstico oportuno y un tratamiento preciso son indispensables en la prevención de los desenlaces fatales y la promoción de un estilo de vida saludable de las personas afectadas.

Los linfomas sonun grupo deneoplasiasmalignasque afectan alsistema linforreticular.1Estas neoplasiashan sido tradicionalmentedivididas entipo Hodgkin ytipo no Hodgkin, ypuede surgir de laslíneas celulares linfocíticas B o T.La mayoría delos linfomasno Hodgkin(LNH) se presentanen los ganglios linfáticos, aunque en raras ocasiones pueden existirsitios primarios extranodales.La localización mandibular primariaes inclusomásrara.2

Caso clínico

Se presenta una paciente de sexo femenino deochenta añoscon unatumoraciónde rápido crecimientoen el ladoderecho de la carade 20días de evolución.La tumoración había aparecido de manera repentina,era moderadamentedolorosay no había respondidoa las terapias convencionales.La paciente tenía la sensibilidadalterada enla región comprometiday dificultad paraabrir la boca.No presentó manifestaciones sistémicascomo fiebreo pérdida de peso.Los antecedentes personales y médicos delapaciente no contribuían para esclarecer el diagnóstico.

El examen clínico revelóuna grantumoraciónextraoraldifusa enla parte central derechay en el tercio inferiorde la cara.Esta tumoración parecíatensa,sincambios secundarios.Había unaumentolocal de la temperaturay dolora la palpación.El tumor erade consistencia firmeynofluctuante.No se pudieron examinar los ganglios linfáticos regionalesdebido a lagran hinchazón.El examen de la región intraoralreveló una inflamación difusadela mucosa bucal del lado derecho, del vestíbuloy de la regiónretromolar.Los dientespróximos a la región inflamada estaban moderadamente cariados y móviles, por lo cual sehabía diagnosticado clínicamente una infección del espacio odontogénico.

Sin embargo, larapidez de la progresión de la lesión,su naturalezasobredimensionada ysufalta de respuestaa los tratamientos convencionaleshicieron pensar en una entidadagresiva, probablementeuntumor maligno,y alentaronuna investigación más profunda.

Una radiografía panorámicamostró una lesiónosteolíticairregularmasiva que ocupaba todo el cuerpo de la mandíbulay su ramaderecha hastael cóndilo mandibular.La tomografía computarizadaconfirmólos hallazgos radiológicos.Los resultados de los exámenes hematológicosse encontrabandentro de los límites normales.

Por medio de una citologíaaspirativa con aguja finase detectaroncélulas linfoides atípicasgrandesen un fondo deeosinófilos dispersos.Una biopsia incisionalmostrócapas difusas decélulas linfoidescon grandesnúcleos vesicularesy nucléolos prominentes.Se encontraron indicios deaumento dela actividad mitóticay áreas de necrosis.Enel análisis inmunohistoquímico, las células tumoralesfueron positivas de forma difusa para elantígeno leucocitario común (CD45).Se llegó al diagnóstico final delinfoma difusode células grandes tipo B (LDCGB). La búsqueda de metástasisno reveló lesiones secundarias.

La paciente fue derivadaa uncentro oncológicoregional, donde realizó seisciclos completos delrégimen estándardequimioterapia CHOP (ciclofosfamida, doxorrubicina, vincristina y prednisona).Al finalizar eltercer ciclode quimioterapia ya se observaba una resolución casi completadel tumor.

Discusión

Los LNH involucran principalmente los ganglios linfáticos.Sin embargo, hasta el 40% de ellos pueden presentarse en forma primaria en sitios extranodales.3-6 La afectación de la cabeza y el cuello es rara y los sitios comunes de aparición son el anillo de Waldeyer, el piso de la boca, las glándulas salivales, la mucosa bucal, los senos paranasales y el hueso.2,7La cavidad oral solamente está involucrada en alrededor del 0.1% al 5% de los casos.4,8,9

La etiología exacta de los linfomas es desconocida.En su aparición han sido implicados la predisposición genética, los estados de inmunodeficiencia como los que padecen los infectados por VIH o los receptores de trasplantes y la translocación cromosómica.1

Descritos por primera vez por Parker y Jackson (1939), los linfomas óseos son poco frecuentes y representan sólo el 5% de todos los LNH extranodales.10Estos linfomas se originan en la cavidad medular del hueso, sin afectar los ganglios linfáticos regionales ni los órganos viscerales por un período de seis meses.11,12Estos tumores son histológicamente similares a los linfomas primarios nodales.13En la región cráneo-facial, los maxilares son un sitio frecuente de aparición de linfomas óseos, y el maxilar superior se ve comprometido con mayor frecuencia que la mandíbula.10,14,15

Los linfomas óseos aparecen en individuos de un amplio rango etario, que comprende desde el primer año de vida hasta los 86 años.2,16Son raros en lactantes y niños, y tienen una tendencia a presentarse en adultos mayores.La distribución por sexo es variable; diversos estudios indican que la relación hombres:mujeres va desde 1.5:117 a 5:118.También se ha observado una relación inversa de 1:3 en otro estudio2.El presente caso constituye una de las presentaciones raras del LNH que afecta al hueso en forma primaria, sin comprometer los ganglios linfáticos ni los órganos viscerales, en una paciente de sexo femenino de 80 años de edad.

Clínicamente, los linfomas de la mandíbula se presentan como una inflamación local con un dolor sordo o constante en los huesos.2Dentro de la boca, se pueden presentar como una masa palpable en las partes blandas.Otros signos y síntomas incluyen dolor dental inexplicable y persistente o movilidad dentaria, parestesia o entumecimiento, la presencia de una masa en las encías o en la concavidad consecutiva a una extracción, ulceraciones persistentes y cambios osteolíticos mal definidos en las radiografías.10,19-27La mayoría de estas características simulan ser alteraciones comunes inflamatorias o benignas de la cavidad oral y pueden ser desorientadoras, como sucedió en el caso actual. El profesional de la salud debe estar alerta y observar estas características con precaución para evitar realizar un diagnóstico más convencional y perder tiempo valioso para el paciente con tratamientos inadecuados.

En la actualidad se utiliza la clasificación de Ann Arbor para la estadificación clínica de los LNH.28Nuestra paciente fue ubicada en el estadio IE A, es decir, compromiso de un único órgano o sitio extranodal, sin síntomas sistémicos.

Alrededor del 80% de los LNH presentan cambios osteolíticos erosivos en las radiografías.Otros tienen una apariencia radiográfica esclerótica o mixta. A veces se pueden observar grandes masas de tejidos blandos extraóseos con destrucción cortical mínima en las radiografías simples.29

En las radiografías panorámicas e intraorales se puede observar específicamente pérdida de la definición cortical del canal dentario inferior, ensanchamiento del canal dentario y del foramen mentoniano, pérdida de la lámina dura y ensanchamiento del espacio del ligamento periodontal.22,30,31Las imágenes por tomografía computarizada (TC) y resonancia magnética nuclear ayudan a visualizar con claridad estos cambios, así como el patrón de destrucción ósea trabecular y el reemplazo de la médula ósea, que generalmente son característicos de los tumores agresivos.32Nuestra paciente presentaba una lesión osteolítica extensa que involucraba casi toda la rama derecha de la mandíbula y se extendía hasta comprometer una parte del cuerpo mandibular.Las imágenes por TC de la lesión nos ayudaron a delinear la lesión en forma neta y a visualizar claramente la arquitectura interna.El aspecto radiográfico tan agresivo nos orientó hacia una enfermedad más grave.

La mayoría de los linfomas se originan en las células de la línea B.El LDCGB representa aproximadamente el 40% de todos los linfomas de células B33 y suele ser agresivo.28Puede aparecer en los ganglios linfáticos o en sitios extranodales y puede causar una destrucción extensa de los huesos afectados.Alrededor del 50% de estos linfomas se diagnostican en el estadio I o II.28,34

Histológicamente, los LDCGB se presentan con capas de grandes células linfoides con núcleos de gran tamaño, que en algunos casos pueden ser escindidas.En algunas lesiones se puede observar un abundante citoplasma, que es pálido o basófilo y la formación de centros germinales.35Los LDCGB se han clasificado de acuerdo con su pronóstico sobre la base de la formación de centros germinales como “similar a centro germinal de células B” (CGB) y “no similar a centro germinal de células B” (no-CGB).Un estudio demostró que el LDCGB oral primario pertenece principalmente al grupo de los no-CGB y presenta un pronóstico más grave en comparación con el grupo de linfomas GCB.36 El antígeno leucocitario común (CD45) es positivo en más del 95% de los casos.37

En la década de 1980, los linfomas fueron clasificados como de bajo grado, de grado intermedio y de alto grado, pero con varias limitaciones.A principios de la década de 1990 se propuso la clasificación REAL, la cual fue aceptada por la OMS luego de sufrir algunas modificaciones de menor importancia.Esta clasificación se basa únicamente en las características histopatológicas e inmunohistoquímicas.1

El diagnóstico de los linfomas óseos se basa en los hallazgos clínicos, radiológicos e histopatológicos.Las exploraciones abdominales, los escaneos PET, los análisis de laboratorio como hemograma completo, lactato deshidrogenasa, análisis de orina, la biopsia aspirativa de médula ósea y las técnicas avanzadas de inmunohistoquímica desempeñan un papel importante en la búsqueda y la obtención de un diagnóstico de certeza.2

En el caso actual, las características histológicas, la inmunohistoquímica y los hallazgos clínicos y radiológicos acentuados fueron de gran valor para llegar al diagnóstico, aunque otras investigaciones no revelaban anormalidades.

La quimioterapia y la radioterapia, utilizadas solas o combinadas, son las principales estrategias de tratamiento.2La terapia combinada proporciona un resultado superior en comparación con la monoterapia.38,39La quimioterapia estándar incluye el régimen CHOP.En los últimos tiempos se ha recomendado emplear la variante RCHOP, es decir, la combinación del régimen CHOP con rituximab (un anticuerpo quimérico anti-CD20).34La radioterapia en el intervalo de 2 400 a 5 600 cGy (35-40 Gy) administrada en fracciones diarias de 180 cGy también ha demostrado ser eficaz.38

El linfoma primario de hueso tiene un pronóstico excelente, más aún en el estadio I y con el uso de la terapia combinada.2,33La tasa de supervivencia a 5 años oscila entre el 50% y el 90%, de acuerdo con los factores pronósticos.33,34,38La tasa de supervivencia a 5 años para los pacientes que presentan estos linfomas en la región maxilofacial es de aproximadamente el 50%.2En el presente caso se logró una excelente respuesta solamente con el régimen de quimioterapia CHOP.La paciente se encuentra en seguimiento y no ha presentado recurrencias hasta la fecha.

Conclusiones

Las formas inespecíficas de presentación de los LNH extranodales de cabeza y cuello, especialmente las que comprometen los maxilares, pueden ser erróneamente interpretadas como otras alteraciones dentarias comunes con cierta frecuencia.Una mayor comprensión de la enfermedad, un diagnóstico oportuno y un tratamiento preciso son indispensables en la prevención de los desenlaces fatales y la promoción de un estilo de vida saludable de las personas afectadas.

Primary Non – Hodgkin’s Lymphoma of the Mandible – A Deceptive Presentation

(especial para SIIC © Derechos reservados)

(especial para SIIC © Derechos reservados)

INTRODUCTION

Lymphomas are a group of malignant neoplasms affecting the lymphoreticular system [1]. They have been conventionally divided into Hodgkin’s and Non-Hodgkin’s types and can arise from B- or T-lymphocytic cell lines. Most non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL) arise in lymph nodes but primary extra nodal sites can be rarely involved. Primary involvement of the jaw bones is further rare [2].

CASE REPORT

An eighty-year-old female patient reported with a rapidly increasing swelling on the right side of face of 20 days duration. The swelling was abrupt in onset, moderately painful and had not responded to conventional therapy. Patient experienced altered sensation in the involved region and difficulty in opening her mouth. There were no systemic manifestations like fever or weight loss. The personal and medical histories of the patient were non-contributory.

Clinical examination revealed a large diffuse extra oral swelling over the right middle and lower third of face. The swelling appeared tense with no secondary changes. There was local rise in temperature and tenderness on palpation. Swelling was firm in consistency and non-fluctuant. The regional lymph nodes were not amenable to examination due to the extensive swelling. Intra oral examination revealed diffuse swelling of right buccal mucosa, vestibule, and retromolar region. The teeth in the vicinity of the swelling were moderately carious and mobile prompting a clinical diagnosis of odontogenic space infection.

However the rapidity, the exaggerated nature of the complaint and its unresponsiveness to conventional therapy induced an impression of an aggressive lesion probably a malignancy and encouraged further investigations.

Panoramic radiograph showed an irregular massive osteolytic lesion occupying the entire body and ramus of mandible extending up to the condyle on the right side. Computed tomography confirmed the radiographic findings. Haematological investigations provided values within normal limits.

Fine needle aspiration cytology depicted atypical large lymphoid cells in a background of scattered eosinophils. Incisional biopsy showed diffuse sheets of lymphoid cells with large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli. There was evidence of increased mitotic activity and areas of necrosis. On immunohistochemical analysis, the tumor cells were diffusely positive for Leukocyte Common Antigen (CD45). A final diagnosis of “Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma” was arrived at.

Metastatic workup revealed no evidence of secondaries.

Patient was referred to a regional oncology centre where six complete cycles of standard regimen of CHOP (Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and Prednisone) were instituted. Almost complete resolution of the swelling was noted as early as the end of 3rd cycle of chemotherapy.

DISCUSSION Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas chiefly involve lymph nodes. However, up to 40% of them may arise from the primary extra nodal sites [3-6]. Head and neck involvement is rare and common sites of emergence are the Waldeyer’s ring, floor of mouth, salivary glands, buccal mucosa, paranasal sinuses, and bone [2,7]. The oral cavity is involved in only about 0.1 to 5% of the cases [4, 8, 9].

The exact aetiology of lymphomas is unknown. A genetic predisposition, immunodeficiency states like HIV infection or transplant recipients and chromosomal translocation have been implicated in their occurrence [1]. First described by Parker and Jackson (1939), bony lymphomas are infrequent and account for only 5% of all extra nodal NHL’s [10]. They arise in the medullary cavity of the bone without involvement of regional lymph nodes or visceral organ over a period of six months [11,12]. Such tumours are histologically similar to primary nodal lymphomas [13]. In the craniofacial region, the jaws are a frequent site for osseous lymphomas, the maxilla more often involved than the mandible [10, 14, 15].

Bony lymphomas occur over a wide age range, spanning from age 1-86 years [2, 16]. They are rare in infants and children and have a tendency to involve older adults. The gender distribution is variable with assorted studies quoting variable male to female ratio ranging from 1.5:1[17] to 5:1[18]. An inverse ratio of 1:3 has also been noted in one study [2]. The present case is one such rare presentation on NHL affecting the bone primarily without involving the lymph nodes or other visceral organs in an 80 yrs old female patient.

Clinically, lymphomas of the jaws present as a local swelling with dull or aching pain in the bone. Intraorally, they may present as a soft tissue palpable mass [2]. Other signs and symptoms comprise unexplained, persistent dental pain and/or tooth mobility, paraesthesia or numbness, a mass on the gingiva or arising from an extraction socket, persistent ulcer and ill defined osteolytic changes on the radiograph [10, 19-27]. Most of these features mimic common benign or inflammatory conditions of the oral cavity and can be misleading as evident in the current case. A vigilant diagnostician should view such features with caution to avoid arriving at a more conventional diagnosis and squandering the patient’s valuable time with inappropriate treatment. The Ann-arbor system is currently used for Clinical staging of the non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [28]. Our patient was staged as IE A, i.e single extra nodal organ or site involvement with no systemic symptoms.

Radiological studies showed that about 80% of them exhibit osteolytic, erosive changes. Others show sclerotic or mixed radiographic appearance. Large extra osseous soft tissue masses with minimal cortical destruction can be observed on plain radiographs [29].

Loss of cortical definition of the inferior alveolar canal, widening of the canal and the mental foramen, loss of lamina dura and widening of the periodontal ligament space have been observed specifically on panoramic and intra oral radiographs [22,30,31]. Computed tomography and Magnetic resonance imaging help in clear visualization of these changes as well as pattern of trabecular bone destruction and marrow replacement that are usually characteristic of aggressive tumours [32]. Our patient presented with extensive osteolytic lesion involving almost the entire right ramus of the mandible extending into part of the body of the mandible. CT imaging of the lesion helped us in clear delineation of the lesion and a lucid visualization of the internal architecture. Such an aggressive radiographic appearance shifted our judgment towards a more grave pathological condition. Majority of Lymphomas originate from B-cell lineage. The Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphomas (DLBCL) account for about 40% of all B-cell lymphomas [33] and are known to be aggressive [28]. They can present in lymph nodes or in extra nodal sites and can produce extensive destruction of the bones in which they occur. About 50% of them present in stage I or II [28, 34]. Histologically they present with sheets of large lymphoid cells with large nuclei which can be cleaved in some cases. Abundant cytoplasm, which is pale or basophilic and germinal centre formation, can be seen in some lesions [35]. DLBCL’s have been prognostically classified based on the germinal centre formation as germinal centre B-cell type (GCB) and Non Germinal centre B-cell type (Non-GCB). One such analysis demonstrated that primary oral DLBCL’s predominantly belong to non-GCB group and exhibit a poor prognosis compared to GCB group [36].

Leukocyte common antigen (CD45) is found positive in over 95% of cases. [37] In the 1980’s lymphomas were classified as low grade, intermediate grade and high grade but with several limitations. REAL classification was proposed in early 1990’s which has been accepted by the WHO after minor modifications. This classification is based only on histopathological and immunohistochemical features [1].

Diagnosis of osseous lymphomas is based on clinical, radiographic and histopathological findings. Abdominal scans, PET scans, laboratory tests like complete hemogram, lactate dehydrogenase, urine analysis, bone marrow aspiration biopsies and advanced immunohistochemistry techniques play a major role in the diagnostic work up and securing an unerring diagnosis [2]. Characteristic histological features including immunohistochemistry coupled with exaggerated clinical and radiological findings were invaluable in acquiring a diagnosis in the current case although other investigations did not divulge any abnormalities.

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy, used alone or in combination are the major modes of treatment [2]. Combination therapy is known to provide a superior outcome when compared to single therapy [38, 39]. The standard chemotherapy includes the CHOP (Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and Prednisone) regimen. A variant of the same RCHOP, i.e in combination with Rituximab (anti CD20 chimeric antibody) has been advocated in recent times [34]. Radiotherapy in the range of 2400 – 5600 c Gy (35-40 Gy) delivered in 180 cGy daily fractions has proven successful [38]. Primary lymphoma of bone has excellent prognosis, more so in stage I and with combination therapy [2, 33]. The 5 year survival rate ranges from 50-90% based on the prognostic factors [33, 34, 38]. In the maxillofacial region, the five year survival rate is approximately 50% [2]. Excellent response was achieved with CHOP chemotherapy regimen alone in the present case. The patient is under follow up and no recurrence has been noted till date. Conclusion Non-specific presentations of extra nodal Non Hodgkin’s lymphomas of head and neck, particularly affecting the jaws can often be misinterpreted as other common dental conditions. Advanced understanding of the disease, timely diagnosis, and precise treatment are indispensable in preventing fatal outcomes and promoting a healthy living of those involved.

Figure 1. Extra oral photograph showing massive swelling over right side of the face

Figure 2. Orthopantomograph showing extensive osteolytic lesion on the right side of mandible

Clinical examination revealed a large diffuse extra oral swelling over the right middle and lower third of face. The swelling appeared tense with no secondary changes. There was local rise in temperature and tenderness on palpation. Swelling was firm in consistency and non-fluctuant. The regional lymph nodes were not amenable to examination due to the extensive swelling. Intra oral examination revealed diffuse swelling of right buccal mucosa, vestibule, and retromolar region. The teeth in the vicinity of the swelling were moderately carious and mobile prompting a clinical diagnosis of odontogenic space infection.

However the rapidity, the exaggerated nature of the complaint and its unresponsiveness to conventional therapy induced an impression of an aggressive lesion probably a malignancy and encouraged further investigations.

Panoramic radiograph showed an irregular massive osteolytic lesion occupying the entire body and ramus of mandible extending up to the condyle on the right side. Computed tomography confirmed the radiographic findings. Haematological investigations provided values within normal limits.

Fine needle aspiration cytology depicted atypical large lymphoid cells in a background of scattered eosinophils. Incisional biopsy showed diffuse sheets of lymphoid cells with large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli. There was evidence of increased mitotic activity and areas of necrosis. On immunohistochemical analysis, the tumor cells were diffusely positive for Leukocyte Common Antigen (CD45). A final diagnosis of “Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma” was arrived at.

Metastatic workup revealed no evidence of secondaries.

Patient was referred to a regional oncology centre where six complete cycles of standard regimen of CHOP (Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and Prednisone) were instituted. Almost complete resolution of the swelling was noted as early as the end of 3rd cycle of chemotherapy.

DISCUSSION Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas chiefly involve lymph nodes. However, up to 40% of them may arise from the primary extra nodal sites [3-6]. Head and neck involvement is rare and common sites of emergence are the Waldeyer’s ring, floor of mouth, salivary glands, buccal mucosa, paranasal sinuses, and bone [2,7]. The oral cavity is involved in only about 0.1 to 5% of the cases [4, 8, 9].

The exact aetiology of lymphomas is unknown. A genetic predisposition, immunodeficiency states like HIV infection or transplant recipients and chromosomal translocation have been implicated in their occurrence [1]. First described by Parker and Jackson (1939), bony lymphomas are infrequent and account for only 5% of all extra nodal NHL’s [10]. They arise in the medullary cavity of the bone without involvement of regional lymph nodes or visceral organ over a period of six months [11,12]. Such tumours are histologically similar to primary nodal lymphomas [13]. In the craniofacial region, the jaws are a frequent site for osseous lymphomas, the maxilla more often involved than the mandible [10, 14, 15].

Bony lymphomas occur over a wide age range, spanning from age 1-86 years [2, 16]. They are rare in infants and children and have a tendency to involve older adults. The gender distribution is variable with assorted studies quoting variable male to female ratio ranging from 1.5:1[17] to 5:1[18]. An inverse ratio of 1:3 has also been noted in one study [2]. The present case is one such rare presentation on NHL affecting the bone primarily without involving the lymph nodes or other visceral organs in an 80 yrs old female patient.

Clinically, lymphomas of the jaws present as a local swelling with dull or aching pain in the bone. Intraorally, they may present as a soft tissue palpable mass [2]. Other signs and symptoms comprise unexplained, persistent dental pain and/or tooth mobility, paraesthesia or numbness, a mass on the gingiva or arising from an extraction socket, persistent ulcer and ill defined osteolytic changes on the radiograph [10, 19-27]. Most of these features mimic common benign or inflammatory conditions of the oral cavity and can be misleading as evident in the current case. A vigilant diagnostician should view such features with caution to avoid arriving at a more conventional diagnosis and squandering the patient’s valuable time with inappropriate treatment. The Ann-arbor system is currently used for Clinical staging of the non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [28]. Our patient was staged as IE A, i.e single extra nodal organ or site involvement with no systemic symptoms.

Radiological studies showed that about 80% of them exhibit osteolytic, erosive changes. Others show sclerotic or mixed radiographic appearance. Large extra osseous soft tissue masses with minimal cortical destruction can be observed on plain radiographs [29].

Loss of cortical definition of the inferior alveolar canal, widening of the canal and the mental foramen, loss of lamina dura and widening of the periodontal ligament space have been observed specifically on panoramic and intra oral radiographs [22,30,31]. Computed tomography and Magnetic resonance imaging help in clear visualization of these changes as well as pattern of trabecular bone destruction and marrow replacement that are usually characteristic of aggressive tumours [32]. Our patient presented with extensive osteolytic lesion involving almost the entire right ramus of the mandible extending into part of the body of the mandible. CT imaging of the lesion helped us in clear delineation of the lesion and a lucid visualization of the internal architecture. Such an aggressive radiographic appearance shifted our judgment towards a more grave pathological condition. Majority of Lymphomas originate from B-cell lineage. The Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphomas (DLBCL) account for about 40% of all B-cell lymphomas [33] and are known to be aggressive [28]. They can present in lymph nodes or in extra nodal sites and can produce extensive destruction of the bones in which they occur. About 50% of them present in stage I or II [28, 34]. Histologically they present with sheets of large lymphoid cells with large nuclei which can be cleaved in some cases. Abundant cytoplasm, which is pale or basophilic and germinal centre formation, can be seen in some lesions [35]. DLBCL’s have been prognostically classified based on the germinal centre formation as germinal centre B-cell type (GCB) and Non Germinal centre B-cell type (Non-GCB). One such analysis demonstrated that primary oral DLBCL’s predominantly belong to non-GCB group and exhibit a poor prognosis compared to GCB group [36].

Leukocyte common antigen (CD45) is found positive in over 95% of cases. [37] In the 1980’s lymphomas were classified as low grade, intermediate grade and high grade but with several limitations. REAL classification was proposed in early 1990’s which has been accepted by the WHO after minor modifications. This classification is based only on histopathological and immunohistochemical features [1].

Diagnosis of osseous lymphomas is based on clinical, radiographic and histopathological findings. Abdominal scans, PET scans, laboratory tests like complete hemogram, lactate dehydrogenase, urine analysis, bone marrow aspiration biopsies and advanced immunohistochemistry techniques play a major role in the diagnostic work up and securing an unerring diagnosis [2]. Characteristic histological features including immunohistochemistry coupled with exaggerated clinical and radiological findings were invaluable in acquiring a diagnosis in the current case although other investigations did not divulge any abnormalities.

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy, used alone or in combination are the major modes of treatment [2]. Combination therapy is known to provide a superior outcome when compared to single therapy [38, 39]. The standard chemotherapy includes the CHOP (Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and Prednisone) regimen. A variant of the same RCHOP, i.e in combination with Rituximab (anti CD20 chimeric antibody) has been advocated in recent times [34]. Radiotherapy in the range of 2400 – 5600 c Gy (35-40 Gy) delivered in 180 cGy daily fractions has proven successful [38]. Primary lymphoma of bone has excellent prognosis, more so in stage I and with combination therapy [2, 33]. The 5 year survival rate ranges from 50-90% based on the prognostic factors [33, 34, 38]. In the maxillofacial region, the five year survival rate is approximately 50% [2]. Excellent response was achieved with CHOP chemotherapy regimen alone in the present case. The patient is under follow up and no recurrence has been noted till date. Conclusion Non-specific presentations of extra nodal Non Hodgkin’s lymphomas of head and neck, particularly affecting the jaws can often be misinterpreted as other common dental conditions. Advanced understanding of the disease, timely diagnosis, and precise treatment are indispensable in preventing fatal outcomes and promoting a healthy living of those involved.

Figure 1. Extra oral photograph showing massive swelling over right side of the face

Figure 2. Orthopantomograph showing extensive osteolytic lesion on the right side of mandible

V G Mahima, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology JSS Dental College and Hospital, 570015, Mysore, India,

e-mail: mahimamds@rediffmail.com

1. Article in edited book - Hematologic Disorders. In: Neville W Brad, Damm Dougloas, Allen C M, Bouquot J E, editors. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, 3rd edition. Noida: Elsevier; 200, p 595-598

2. Journal article - Pazoki A, Jansisyanont P, Ord R A. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the jaws: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003; 61: e112-117

3. Journal article - d’Amore F, Christensen BE, Brincker H et al. Clinicopathological features and prognostic factors in extra nodal non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Danish LYFO Study Group. Eur J Cancer 1991; 27:1201–1208.

4. Journal article - Freeman C, Berg JW, Cutler SJ. Occurrence and prognosis of extra nodal lymphomas. Cancer 1972; 29:252–260.

5. Journal article - Newton R, Ferlay J, Beral V et al. The epidemiology of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: comparison of nodal and extra-nodal sites. Int J Cancer 1997; 72:923–930.

6. Journal article - Otter R, Gerrits WB, Sandt MM et al. Primary extra nodal and nodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. A survey of a population-based registry. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1989; 25:1203–1210.

7. Journal article - GK Maheshwari, HA Baboo, U Gopal, MK Wadhwa. Primary extra-nodal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the cheek. J of Postgraduate med 2000; 46(3):211-2

8. Journal article - Tomich CE, Shafer WG. Lymphoproliferative disease of the hard palate: A clinicopathologic entity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1975; 39:754

9. Journal article - Fukada Y, Ishida T, Fujimoto M. Malignant lymphoma of the oral cavity: Clinicopathologic analysis of 20 cases. J Oral Pathol 1987; 6:8

10. Journal article - Gusenbauer AW, Katisikeris NF, Brown A. Primary lymphoma of the mandible: Report of case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1990; 48:409

11. Journal article - Boston HC, Dahlin DC, Ivins JC, et al. Malignant lymphoma (so called reticulum cell sarcoma) of bone. Cancer 1974; 34:1131

12. Journal article - Pettit CK, Zukerberg LR, Gray MH, et al. Primary lymphoma of bone: A B cell neoplasm with a high frequency of multilobated cell. Am J Surg Pathol 1990; 4:329.

13. Article in edited book - Huvos AG. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of bone. In: Bone Tumours: Diagnosis, Treatment and Prognosis (ed 2). Philadelphia, PA, Saunders 1991; 625-637

14. Article in edited book - Henry K. Neoplastic disorders of lymphoreticular tissue. In: Henry K, Symmers WSTC (eds): Systemic Pathology (ed 2). Edinburgh, Scotland, Churchill Livingstone 1992; p 611-660

15. Journal article - Robins KT, Fuller LM, Mening J, et al. Primary lymphoma of the mandible. Head Neck Surg 1986; 8:192

16. Journal article - Ostrowski ML, Unni KK, Banks PM, et al. Malignant lymphoma of bone. Cancer 1986; 58:2646

17. Journal article - Clayton F, Butler JJ, Ayala AG, et al. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in bone: Pathologic and radiologic features with clinical correlates. Cancer 1987; 60:2494

18. Journal article - Potdar GG. Primary reticulum-cell sarcoma of bone in Western India. Br J Cancer 1970; 24:48

19. Journal article - Park YW. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the anterior maxillary gingiva. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998; 119:146

20. Journal article - Eisenbud L, Sciubba J, Mir R, et al. Oral presentation in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: A review of thirty-one cases; part 2. Fourteen cases arising in bone. Oral Surg 1983; 56:272

21. Journal article - Barber DH, Stewart JCB, Baxter WD. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma involving the inferior alveolar canal and mental foramen: Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1992; 50:1334

22. Journal article - Barker GR. Unifocal lymphoma of the oral cavity. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1984; 22:426

23. Journal article - Nocini P, Muzio LL, Fior A, et al. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the jaws: Immunohistochemical and genetic review of 10 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000; 58:636

24. Journal article - Ardekian L, Peleg M, Samet N, et al. Burkett’s lymphoma mimicking an acute dentoalveolar abscess. J Endod 1996; 22:697

25. Journal article - Parrington SJ, Punnia-Moorthy A. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the mandible presenting following tooth extraction. Br Dent J 1999; 187:468

26. Journal article - Mills LJ, Sadeghi E, Sampson E. Palatal nonspecific granulomatous lesion preceding diagnosis of malignant lymphoma. Gen Dent 1995; 43:28

27. Journal article - Liu RS, Liu HC, Bu JQ, et al. Burkett’s lymphoma presenting with jaw lesions. J Periodontal 2000; 71:646

28. Article in edited book - ‘Lymphoid Lesions’ Oral Pathology Clinical Pathologic Correlations. Regezi, Sciubba and Jordan. Fifth edition, China, Elsevier, 2008, 220-229

29. Journal article - Edeiken-Monroe B, Edeiken J, Kim EE. Radiologic concepts of lymphoma of bone. Radiol Clin North Am 1990; 28:841

30. Journal article - Stolarski CR, Boguslow BI, Hoffman CH, et al. Small-cell non-cleaved non-Hodgkins lymphoma of the mandible in previously unrecognized Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection: Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997; 55:853

31. Journal article - Yamada T, Kitagawa Y, Ogasawara T, et al. Enlargement of mandibular canal without hypesthesia caused by extra nodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: A case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radol Endod 2000; 89:388

32. Journal article - Yasumoto M, Shibuya H, Fukuda H, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the gingiva: MR evaluation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998; 19:723

33. Journal article - L Djavanmardi, N Oprean et al. Malignant non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) of the jaws: A review of 16 cases. J of Cranio-Maxillofac Surg 2008; 36: e410-414.

34. Article in edited book - Wenig B M. ‘Tumours of Upper Respiratory Tract’ in Diagnostic Histopathology Of Tumours. Fletcher C D M, 3rd edition, Vol II, China, Elsevier, 2007, 124- 27

35. Article in edited book - R Rajendran. ‘Benign and malignant tumours of the Oral cavity’. In: Shafer’s Text Book of Oral Pathology. Shafer, Hine and Levy. Sixth edition, Delhi, Elsevier, 2006, 175-180

36. Journal article - Indraneel Bhattacharyya, Hardeep K. Chehal et al. Primary Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma of the Oral Cavity: Germinal Centre Classification. Head and Neck Pathol (2010) 4:181–191

37. Article in edited book - L M Weiss, W C Chan, B Schnitzer. ‘Lymph Nodes’. In: Anderson’s pathology. I Damjanov, J Linder. 10th edition, Vol I, Missouri, Mosby Year Book, 1996, 1115-1200

38. Journal article - Kathryn Beal, Laura Allen, Joachim Yahalom. Primary Bone Lymphoma: Treatment Results and Prognostic Factors with Long-Term Follow-up of 82 Patients. Cancer 2006; 106:2652

39. Journal article - Thomas P. Miller, Steve Dahlberg et al. Chemotherapy alone compared with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy for localized intermediate- and high-grade non-hodgkin’s lymphoma The New Eng J of Med 1998; 339[1], 21-26

Artículos publicados por el autor

(selección)

Mahima VG, Karthikeya Patil, Anudeep Raina Extranodal Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma- an unfamiliar presentation in the oral cavity: a case report International journal of clinical cases and investigations 1(1):1-6, 2010

Mahima VG, Karthikeya Patil, Suchetha N Malleshi. A clinicohistopathologic diagnosis of imitable presentation of orofacial granulomatosis International journal of clinical cases and investigations 1(1):1-7, 2010

Mahima VG, Anudeep Raina, Karthikeya Patil Mouth is the mirror of the body: Diabetes Mellitus International journal of clinical cases and investigations 1(1):5-12, 2010

Dr Mahima V G, Dr Karthikeya Patil, Dr Srikanth H S Mental foramen for gender determination: A panoramic radiographic study Medico-Legal Update 9(9):33-35, 2009

Karthikeya Patil, V.G. Mahima, R.M. Prathibha Rani. Oral histoplasmosis Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology 13(13):157-159, 2010

Patil K, Mahima V G, Gupta B. Gorlin Syndrome: A Case Report Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry :198-203, 2005

Karthikeya Patil, Mahima V G, Shalini Kalia. Papillary Cystadenoma lymphomatosum: Case Report and Review of Literature Indian Joural of Dental Research 16(16):153-158, 2005

K Patil, Mahima V G, Shetty S K, Lahari K Facial Plexiform Neurofibroma in a child with Neurofibromatosis type- I : A case report Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry 25:30-34, 2007

K Patil, Mahima V G, Jayanth B.S, Ambika L Burkitt's Lymphoma in an Indian Girl - a case report Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry :194-199, 2007

Karthikeya Patil, Mahima V Guledgud, Srikanth H. Srivathsa. Doppler Ultrasound for the Diagnosis of Intraparotid Hemangioma Journal for Vascular Ultrasound 34(34):74-76, 2010

Mahima VG, Karthikeya Patil, Anudeep Raina Extranodal Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma- an unfamiliar presentation in the oral cavity: a case report International journal of clinical cases and investigations 1(1):1-6, 2010

Mahima VG, Karthikeya Patil, Suchetha N Malleshi. A clinicohistopathologic diagnosis of imitable presentation of orofacial granulomatosis International journal of clinical cases and investigations 1(1):1-7, 2010

Mahima VG, Anudeep Raina, Karthikeya Patil Mouth is the mirror of the body: Diabetes Mellitus International journal of clinical cases and investigations 1(1):5-12, 2010

Dr Mahima V G, Dr Karthikeya Patil, Dr Srikanth H S Mental foramen for gender determination: A panoramic radiographic study Medico-Legal Update 9(9):33-35, 2009

Karthikeya Patil, V.G. Mahima, R.M. Prathibha Rani. Oral histoplasmosis Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology 13(13):157-159, 2010

Patil K, Mahima V G, Gupta B. Gorlin Syndrome: A Case Report Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry :198-203, 2005

Karthikeya Patil, Mahima V G, Shalini Kalia. Papillary Cystadenoma lymphomatosum: Case Report and Review of Literature Indian Joural of Dental Research 16(16):153-158, 2005

K Patil, Mahima V G, Shetty S K, Lahari K Facial Plexiform Neurofibroma in a child with Neurofibromatosis type- I : A case report Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry 25:30-34, 2007

K Patil, Mahima V G, Jayanth B.S, Ambika L Burkitt's Lymphoma in an Indian Girl - a case report Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry :194-199, 2007

Karthikeya Patil, Mahima V Guledgud, Srikanth H. Srivathsa. Doppler Ultrasound for the Diagnosis of Intraparotid Hemangioma Journal for Vascular Ultrasound 34(34):74-76, 2010

Está expresamente prohibida la redistribución y la redifusión de todo o parte de los

contenidos de la Sociedad Iberoamericana de Información Científica (SIIC) S.A. sin

previo y expreso consentimiento de SIIC.

ua91218